Stefania Urist wants people to think about the importance of trees.

A resident of Vermont, Stefania Urist is keenly interested in trees and old-growth forests. She was exploring Winterthur in 2020 learning from staff conservators how to preserve outdoor sculptures, when she saw an Instagram post that changed her direction. In the post, there was a photo of a staff member counting the rings of a 300-year-old oak that had been felled by a tornado that summer. “The tree was a wide as the staff member was tall,” Urist. “I knew right away it was old. When I saw it, I said, ‘I need a piece of that.’”

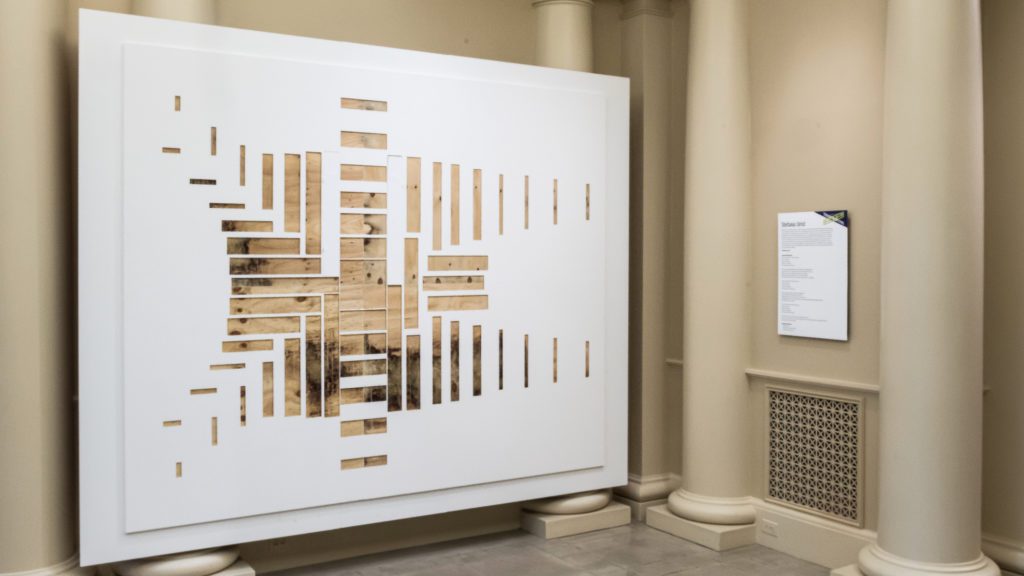

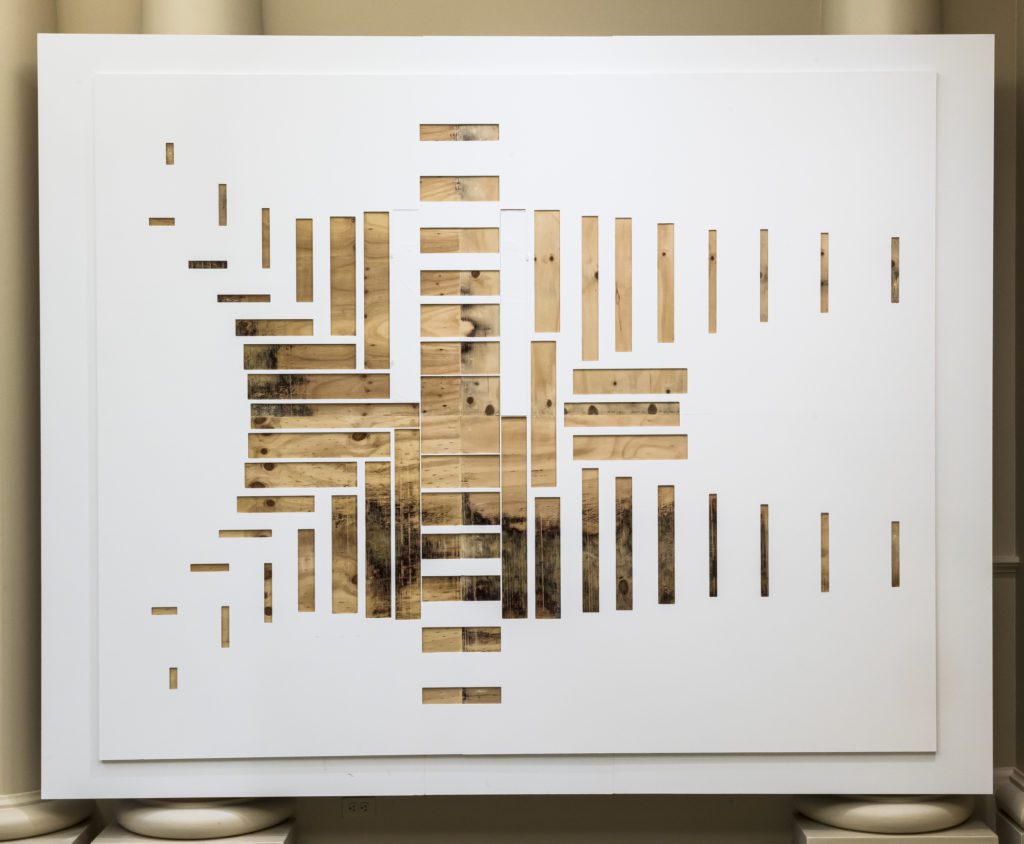

Among other things, Urist’s art addresses ideas about the environment, in part by using materials in unusual ways. She used parts of the tree she discovered on Instagram, known as the Brown’s Meadow Oak, to create one of two related works in Transformations. Fragmented Memories, made of paper over wood, expands a milling pattern into pieces the viewers can remove and keep, thus involving them in the work’s evolution. Bonded Memories, made of paper embossed with the oak’s rings, imagines the tree reassembled.

“I wasn’t searching for something like that tree at that time,” Urist says. “But I was letting my research guide me in terms of being interested in old-growth trees. And I was actually trying to find some up here in Vermont, so it was kind of serendipitous.”

The work is now on display in the Winterthur galleries area as part of Transformations: Contemporary Artists at Winterthur, which showcases current responses to the traditional forms and objects the institution is known for. The six artists currently represented in Transformations were all part of Winterthur’s Maker-Creator Research Fellowship, a program that provides a stipend and gives access to Winterthur and its staff for research that inspires the work of creative professionals. Also on view is Urist’s Mapping the Impact, a sculpture of leaded glass, copper, and reclaimed wood that resembles a tree stump, and The Ceiling, on the patio of the Galleries Reception Atrium entrance.

It was living in the Green Mountain State that kicked Urist’s interest in trees into high gear. Since colonial days, Vermont has been clear cut many times for mining, agriculture, settlement, and other purposes. Much forest has grown back, but there is no true old growth, so the ecosystem has changed. Urist wants to call attention to the intelligence of trees—the way they communicate chemically, the way they support each other, and their key role in healthy ecosystems. Art is one way to do that.

“I came to the milling patterns by being interested in the interaction between humans and nature, how we turn natural, curvy, inconsistent shapes into linear, industrialized products,” Urist says. “You can see different artistic shapes in there, almost like art deco patterns, and I found that really beautiful but also really sad.”

In other work, Urist lifts the “fingerprints” of trees. From freshly cut logs and stumps that still ooze sap, Urist imprints paper, then dusts it with graphite to highlight the ring pattern. Each is as unique as a human fingerprint.

“My interest in art in general is about connecting, seeing patterns in life and nature that maybe other people don’t see, or just connecting them in different ways than other people do,” Urist says. “The tree rings are the lifeline and literal timeline of the tree made into a physical shape. I just want people to think about it in a different way, think about our own consumption and how we use these beings to be objects and building materials when they existed for so long before that.”

Urist’s work, and the work of the other Transformations artists, is currently on view in the galleries area.