Jacqueline Kennedy’s 1962 televised look inside the White House influenced a generation. It took some help from Winterthur.

When First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy gave television viewers their first look at the newly restored interior of the White House, she broke ground in many ways—and she made a lasting impression.

“A Tour of the White House with Mrs. John F. Kennedy” is considered by some television scholars to be the first prime time documentary targeted to a female audience. Broadcast on the CBS and NBC networks on February 14, 1962, it was the most-watched television program of its day. By the time it was shown on ABC four days later, it had drawn 80 million viewers.

“My mother was still talking about it thirty years later, when I was contemplating a thesis topic and realized the connection between Winterthur and the White House project,” says Elaine Rice Bachmann, a former student in the Winterthur Program in American Material Culture and curator of the upcoming exhibition Jacqueline Kennedy and H. F. du Pont: From Winterthur to the White House. “Because the medium of television was well established by 1962, with one in nearly every home, and in a time before multiple channels were available, it meant that nearly every American watched this program.” Due to syndication, people in 50 countries eventually were able to view the tour.

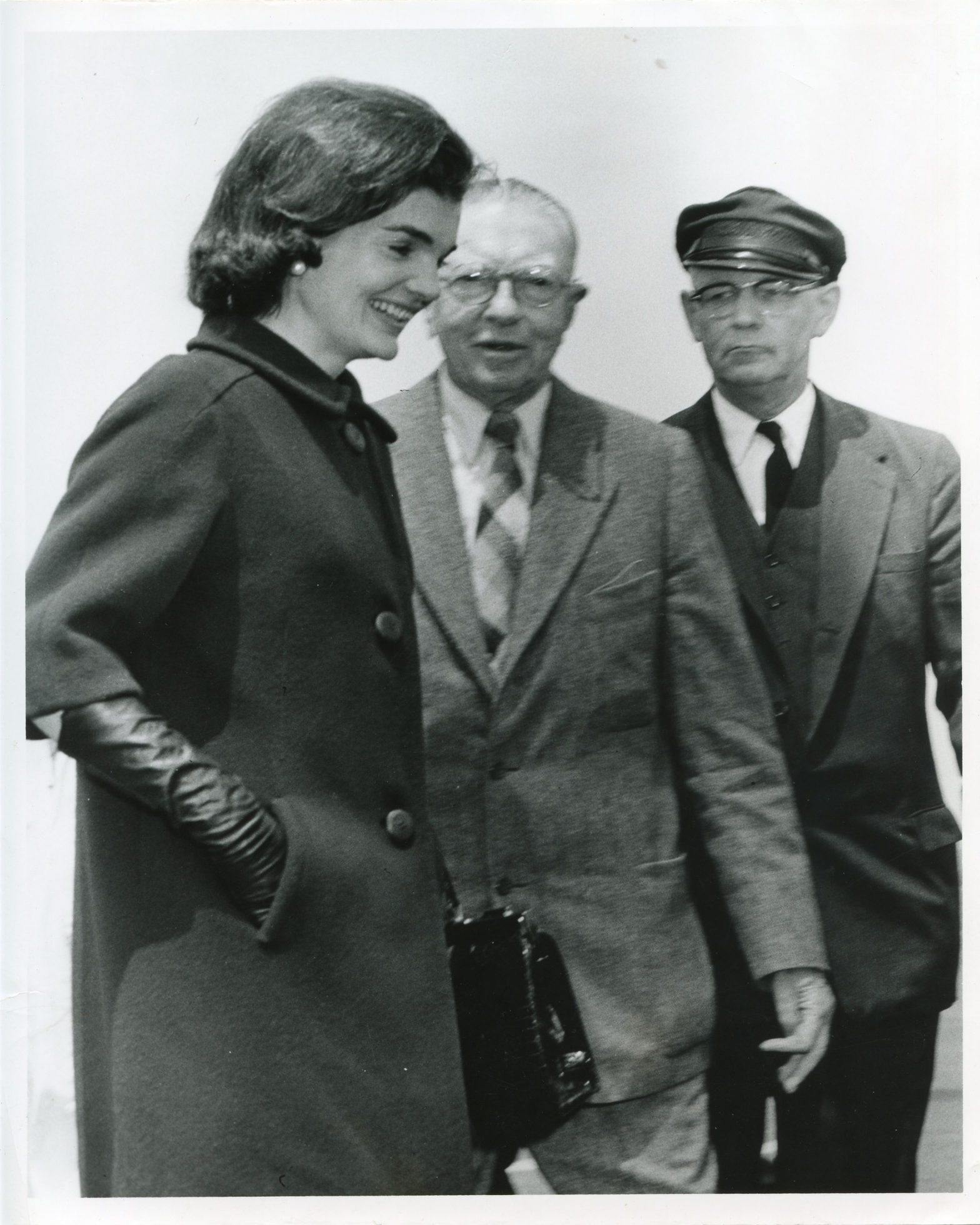

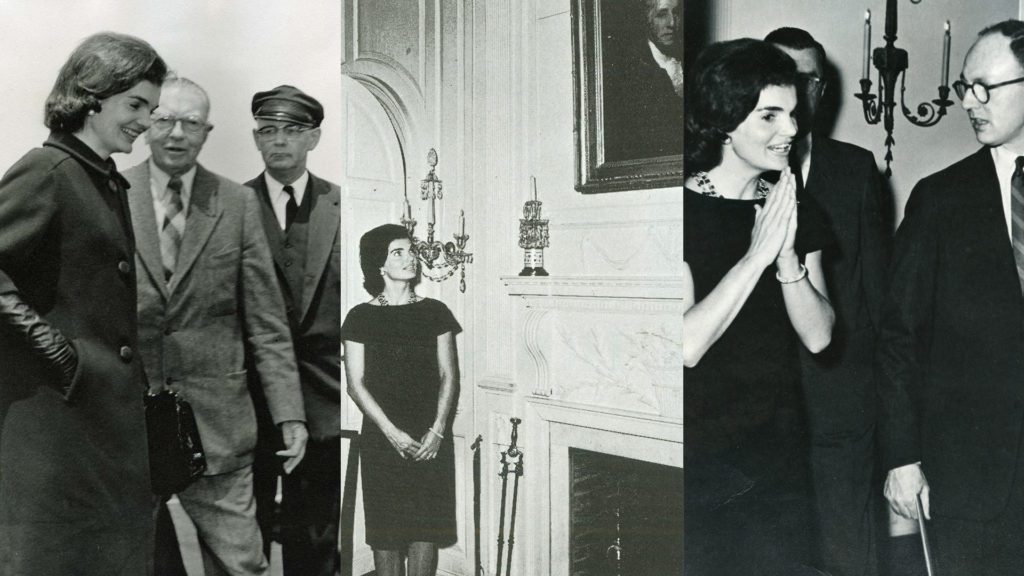

Winterthur founder Henry Francis du Pont played a key role in the First Lady’s famous restoration of 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. Kennedy, determined to turn the faded home into a place of beauty and historic value that was worthy of a head of state, undertook the project soon after her husband, John F. Kennedy, was inaugurated in January 1961. She personally invited du Pont, then considered the nation’s greatest collector of, and foremost authority on, American historical decoration, to chair her Fine Arts Committee. The committee—suggested by Winterthur Director Charles F. Montgomery—searched for and acquired the art and antiques needed to realize Kennedy’s vision. Du Pont gave scholarly credibility to the effort.

Seeing a need for a permanent steward of the White House collection, Kennedy named Lorraine Waxman Pearce, a graduate of the Winterthur Program in Early American Culture who worked as a registrar at Winterthur, the first curator of the White House in March 1961. By September of that year, Congress enacted legislation designating the White House a museum, and in November, the White House Historical Association was chartered.

“Everything in the White House must have a reason for being there,” Kennedy told Life magazine at the time. “It would be sacrilege merely to redecorate it—a word I hate. It must be restored, and that has nothing to do with decoration. That is a question of scholarship.”

Within the year, cameras captured the big reveal.

“I think what is important to acknowledge is that this was not just ‘celebrity’ watching, although the enormous popularity of Mrs. Kennedy cannot be underestimated,” Bachmann says. “It was considered an important educational event, watched by many children. The media widely applauded the First Lady for her efforts to share White House history and American history with the public.”

Kennedy’s televised tour was not scripted, Bachmann points out. The First Lady wrote her own notes, which she studied in advance of the taping. She specified the route through the White House—through the State Dining Room, and then through the iconic Red, Blue, and Green rooms—and decided what furnishings and art to discuss. “The producers documented that they never needed to reshoot any scenes with her,” Bachmann says. “She was a one-take wonder.” The performance earned Kennedy an honorary Emmy.

Three pages of Mrs. Kennedy’s handwritten notes for the program, generously loaned by the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, will be on display in the Winterthur exhibition, as will correspondence between Kennedy and du Pont from the Winterthur collection.

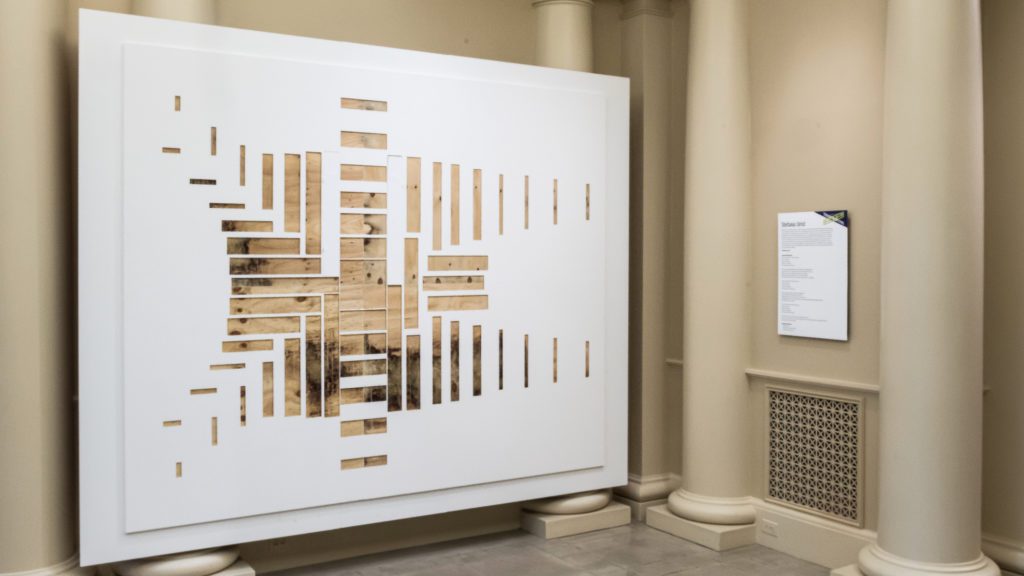

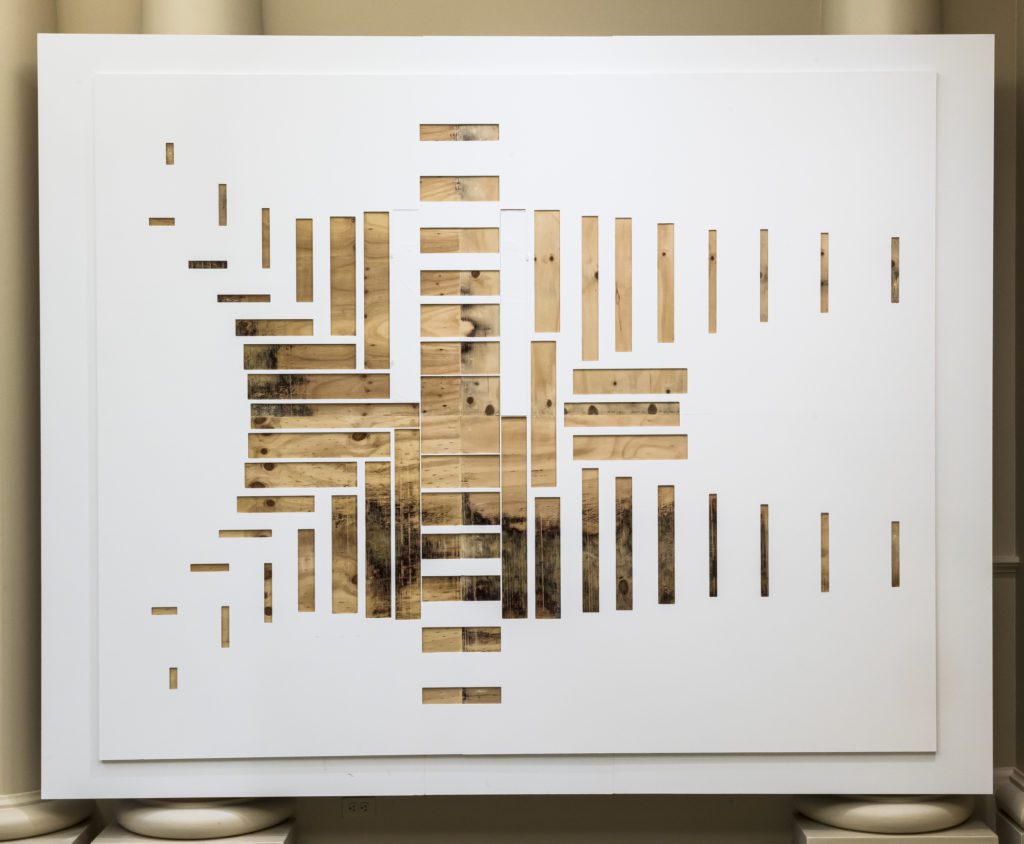

The story of Kennedy and du Pont’s relationship and his influence on the restoration will also be told through beautiful objects, photos, and other documents. Jacqueline Kennedy and H.F. du Pont: From Winterthur to the White House opens May 7, 2022.

Until then, you can celebrate the 60th anniversary of the broadcast—and Valentine’s Day—by watching portions of “A Tour of the White House with Mrs. John F. Kennedy” via CBS’s Youtube.com channel.