April 7, 2025

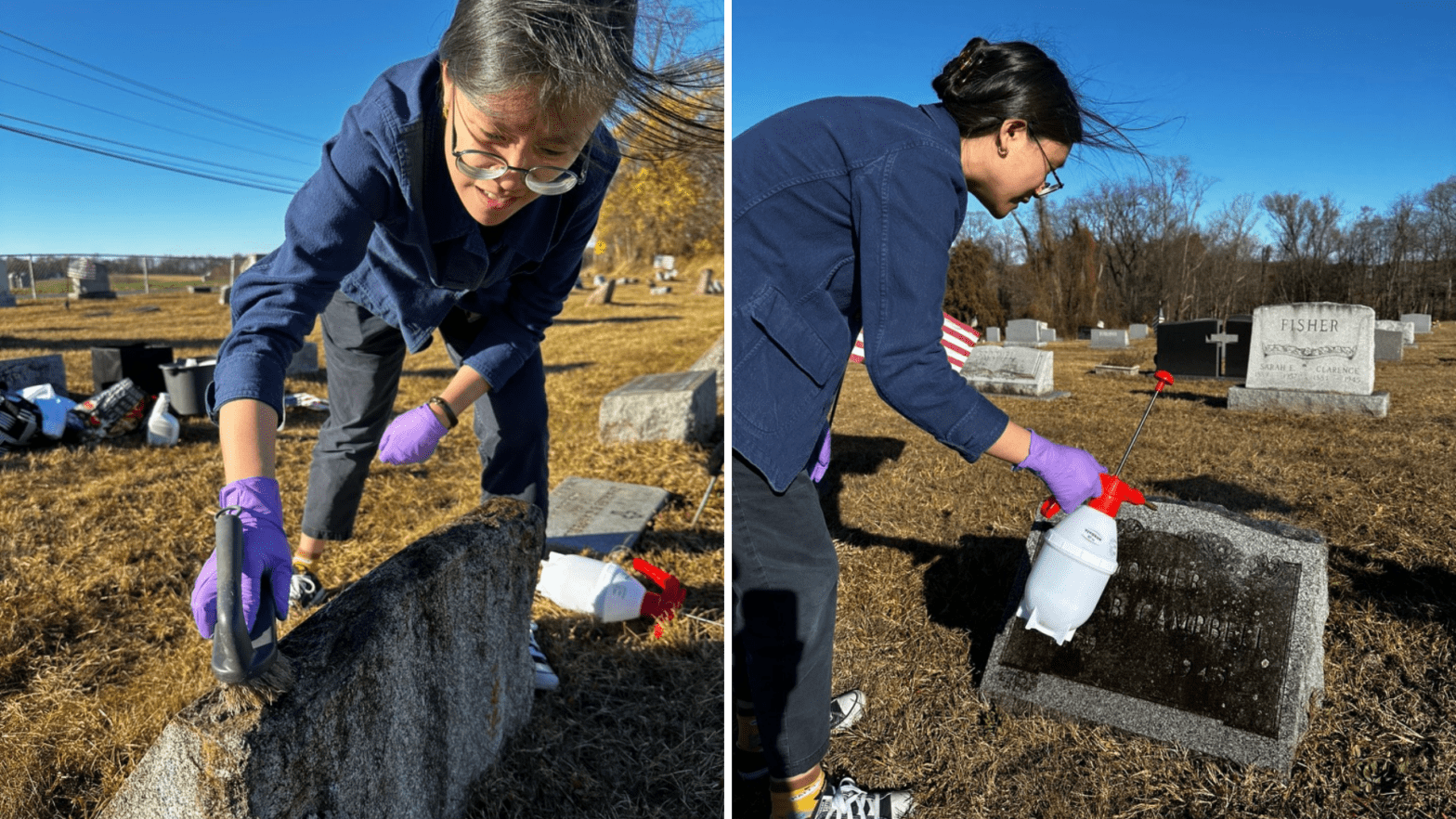

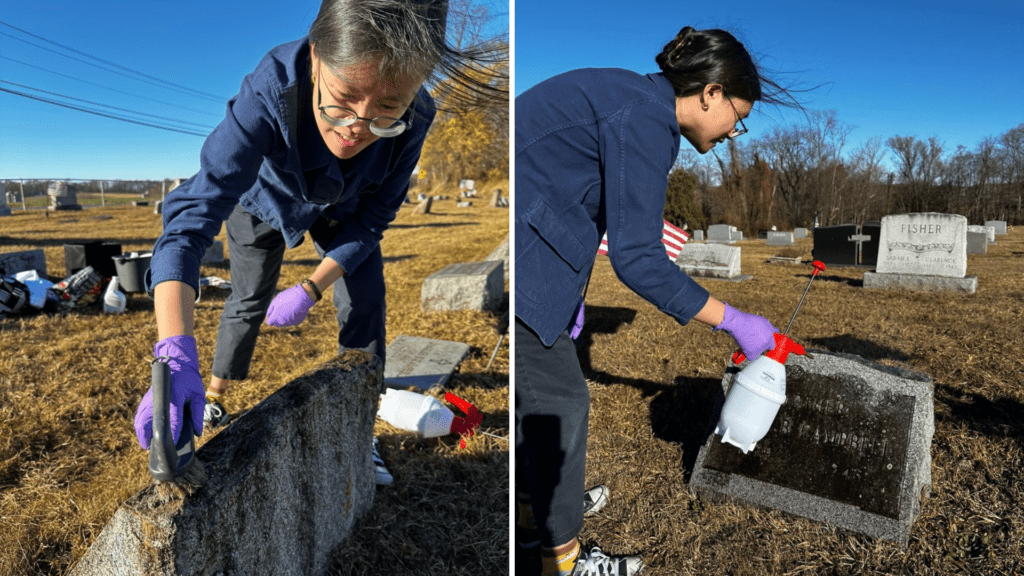

Late last week we learned that our $71,880 multiyear federal grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH), which supports Winterthur’s independent research fellowship program, has been terminated effective immediately. The term for this grant was approved in 2023 to fund $20,000 stipends for three visiting research fellows over three years, along with related administrative costs.

We’ve assured our current NEH fellow that we’ll secure alternative funding to support her research, which is scheduled to end in mid-June. We’ve also committed to funding the next fellowship through other means if the candidate accepts the position that we offered a few days prior to receiving the grant termination notice from DOGE.

Given the current situation, we’ve been taking proactive steps to reduce Winterthur’s reliance on federal and state grants. Our annual operating budget has typically included $300,000 to $600,000 in funding from various sources, including the NEH, the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS), the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), the National Park Service, Delaware Humanities, and the Delaware Division of the Arts.

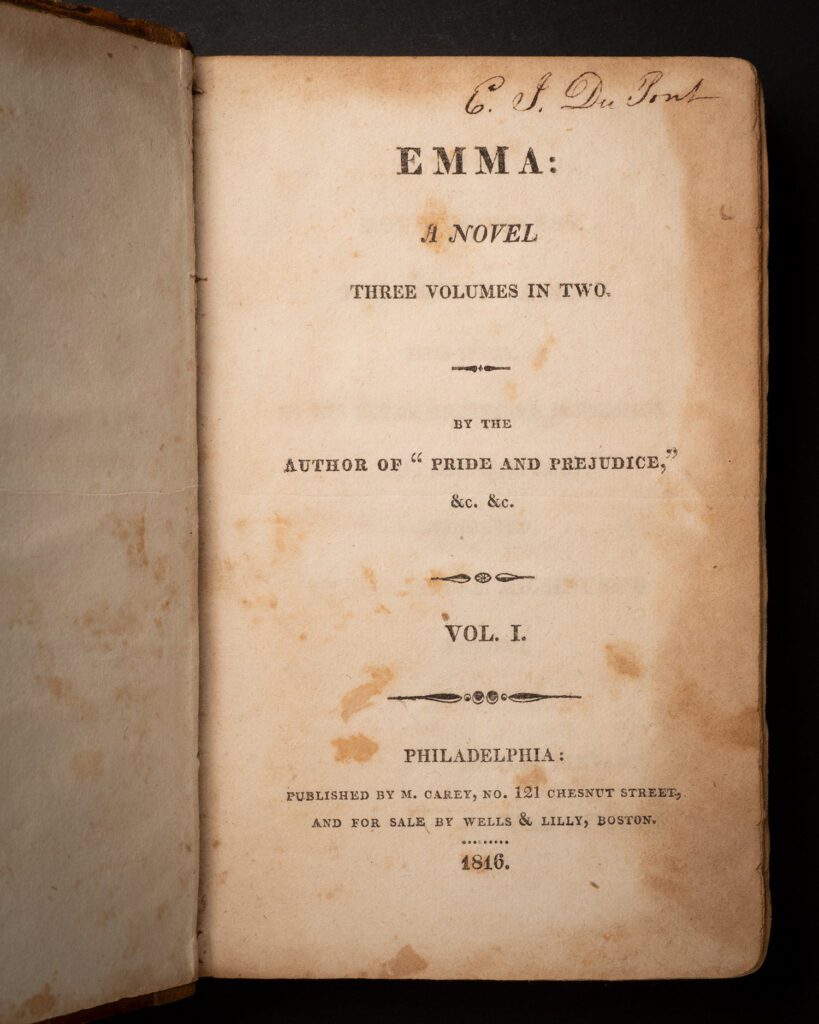

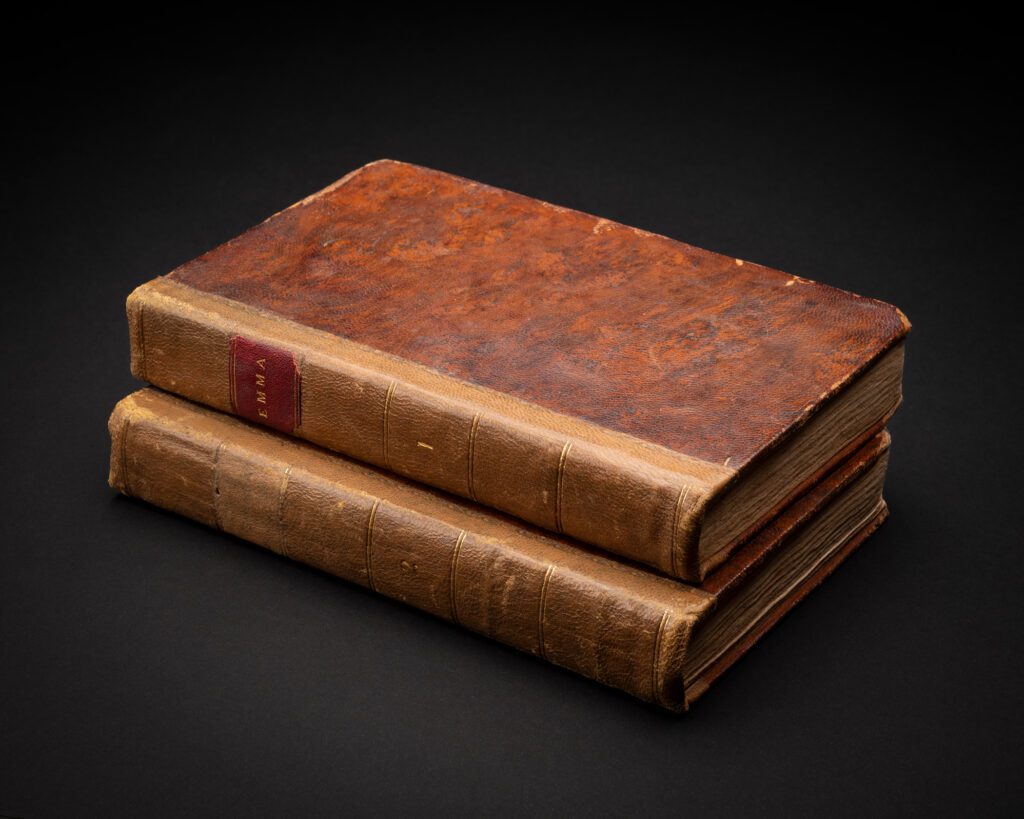

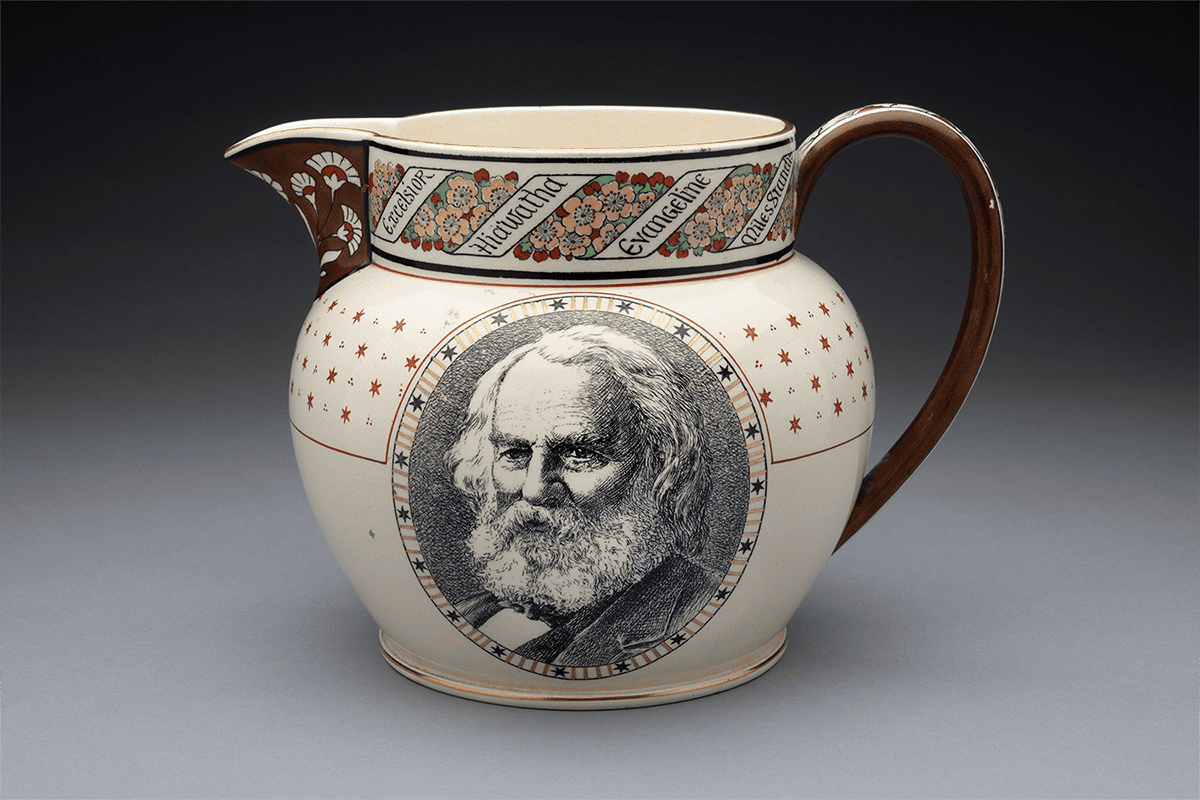

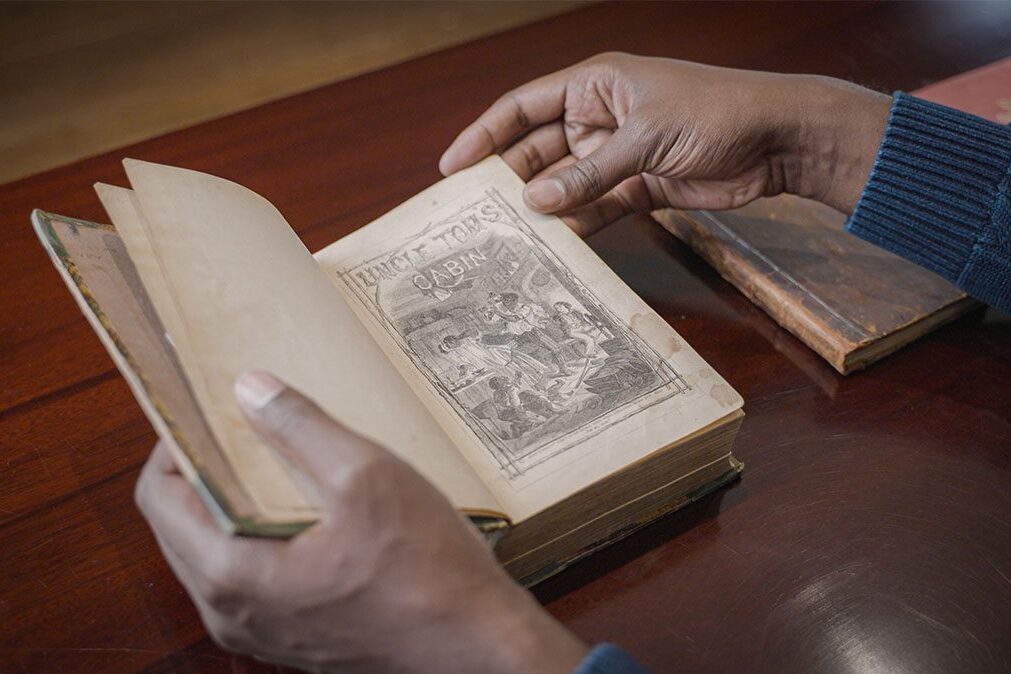

Winterthur has used NEH grants to fund exhibition and research project planning, large cataloguing projects, and to underwrite the prestigious fellowships we’ve offered through Fellowship Programs at Independent Research Institutions (FPIRI) back to 2004 and beyond. Federal funds enabled us to make description and access enhancements to the museum collections database of more than 90,000 objects.

In addition to the direct impact on Winterthur’s budget allocation, we’ve also been notified that the University of Delaware’s NEH grant funds have been terminated. Among other university programs, this cut impacts some students in the joint graduate-level Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation. The university is working to identify new funding streams, and Winterthur will support those efforts in whatever way we can.

With continued federal and state pass-through funding in doubt for the foreseeable future, we will recalibrate and find ways to continue to offer our programs. I’m committed to working with all of you so that our important programs and research will find support through other avenues.

To start, we’ve spoken with U.S. Senator Chris Coons and other state officials to share the impact of these federal cuts on Winterthur’s programs and people. We’re also communicating with our Board of Trustees, partners, and supporters. We will continue this advocacy.

We also know our strength lies in our community—people like you who care deeply about our mission. Here are the ways you can help:

Stay Informed: We will keep you updated. In addition, you can visit the National Humanities Alliance and Delaware Humanities websites.

Engage with Our Programming: Support and attend exhibitions and events.

Advocate for Winterthur & Other Cultural Institutions: Champion our cause within your networks.

Thank you for your ongoing support. Together, we’ll continue to thrive and ensure current and future generations enjoy Winterthur’s gardens, museum, library, cultural and educational offerings.

Learn more about our independent research fellowship program and or contribute by visiting https://my.winterthur.org/donate/q/academic-programs .