By Camille Williams, curatorial intern at Winterthur Museum, Garden and Library

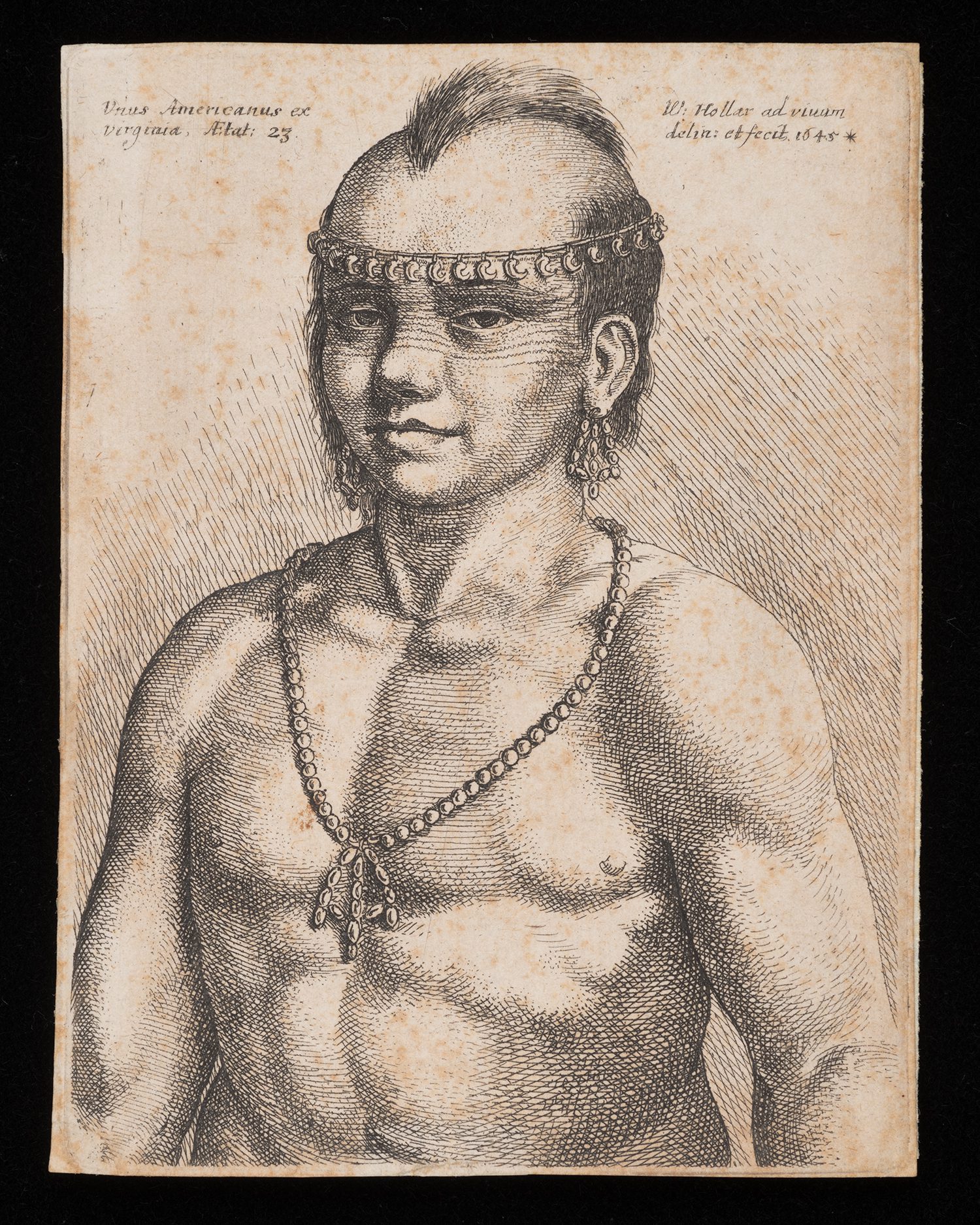

This recently acquired half-length portrait engraving by artist Wenceslaus Hollar portrays a once-known young Native American man, thousands of miles removed from home, caught up in the Dutch Empire’s fraught colonization of North America (fig. 1). Measuring only 4 inches by 3 inches, this rare depiction came by the deft hand of 17th-century Europe’s most influential and prolific printmaker. Prague-born Hollar, who enjoyed steady patronage in Germany, England, and the Netherlands, distributed his prints widely. But who was this Native man?

With his inscription in the print’s top left, Hollar recorded “Vnus Americanus ex / Virginia, Ætat: 23” or “An American from Virginia, aged 23”. At this time, Europeans used “Virginia” to refer to the territory along the eastern coastline of North America; the subject of the print likely belonged to the Munsee Delaware Algonquin-speaking people who inhabited much of the New Netherlands colony, from modern-day New York to Delaware. From the top right inscription, “Hollar ad vivum / delin: et fecit, 1645,” we know that Hollar drafted and executed the etching in 1645 when he was likely in Antwerp, Belgium.[i]

Using a precise cross-hatching technique, Hollar approached the subject with his characteristic scientific accuracy, drawing attention to the sitter’s musculature, facial tattoos, and shaved hairstyle. The subject wears a headdress of animal teeth, and his earrings and necklace consist of beads and shells. Known as wampum or “sewant” by the Dutch, these colored beads and shells served not only as currency for trade but also held spiritual importance for those who fashioned them.[ii] With his half-open, almond-shaped eyes and closed mouth with upturned corners, the subject is depicted with a peaceful expression. His direct but nonconfrontational gaze invites the viewer to look upon the man with respect and dignity. Yet this representation conceals the dark reality of the circumstances that brought him to Europe.

Scholar George Hamell identified the sitter as a Munsee warrior named Jaques. Legal records from September 1644 document that two soldiers of the West India Company entered into a contract with a Dutchman to exhibit a “wilde Indiaen”—or “savage Indian” named Jaques in exchange for money. According to the contract, Jaques sailed with the men to the Netherlands on the ship Count Maurits in 1644.[iii]

Jaques may have fought in Kieft’s War, a series of Dutch-Indian conflicts in present-day New York between 1643 and 1645, resulting in the loss of more than 1,000 Native lives. Sensationalized accounts of massacres spread across Europe, which perpetuated stereotypes of “cruel” and “ferocious Indians.”[iv] Other sources attested to the kidnapping of Native Americans to the Netherlands, as was the case with Jaques.[v]

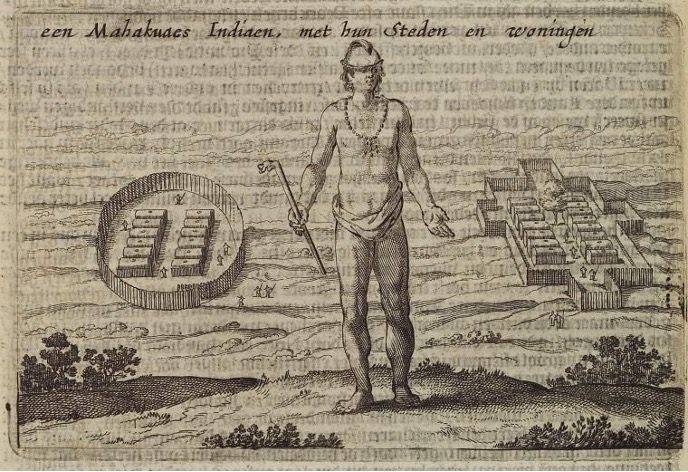

Regardless of whether the man depicted here is truly Jaques, his likeness continued to circulate and came to represent Native Americans in the New Netherlands. When a Dutch missionary in Albany named Johannes Megapolensis wrote to his friends in Holland of his encounters with “savage” and “heathen” Mohawks and Mohicans in August 1644, they published them with a full-length engraving depicting a Native man strikingly similar to the one in Hollar’s print. The reverse orientation of the image and the decreased detail of the hatch marks suggest that the engraver traced and transferred Hollar’s image. Several times over the ensuing centuries, publishers reproduced these textual and visual accounts of the New World, extending the wider impact of Hollar’s original 1645 print.

Today, as Hollar’s print remains coveted in museum collections, it is important to remember Jaques—both the vitality of his image and the dispossession and erasure endured by indigenous people.

[i] Richard Pennington, A Descriptive Catalogue of the Etched Work of Wenceslaus Hollar, 1607–1677 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982), cat. no. 2009, 317.

[ii] George Hamell, “The Iroquois and the World’s Rim: Speculations on Color, Culture, and Contact,” American Indian Quarterly 16, no. 4 (1992): 451–69.

[iii] George Hamell, “Jaques a Munsee from New Netherland,” unpublished; evidence from the translated Dutch contract is published in “Jaques,” New York Genealogical and Biographical Society, https://www.newyorkfamilyhistory.org/new_netherland_settlers/jaques#ftnt1.

[iv] Robert Grumet, The Munsee Indians (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2009), 54–67.

[v] “In October 1644, The Eight Men, an elected advisory council in the New Netherlands, complained about the practice of gifting Native prisoners of war to soldiers,” New York Genealogical and Biographical Society, https://www.newyorkfamilyhistory.org/new_netherland_settlers/jaques#ftnt1