By Molly Mapstone, Winterthur Academic Affairs Intern

Our memories are wells of invaluable information. The basic facts of our lives, skills we learned in school, and important events are all stored in our minds and inflected by our unique experiences and perspectives. Through oral history, we record and collect these memories for future generations. Following the death of their colleague, Rutherford John Gettens, early career art conservators Tom Chase and Joyce Hill Stoner spearheaded an oral history project to collect firsthand accounts of their profession.

On September 4, 1975, Chase and Stoner conducted a roundtable discussion at a conservation conference with conservators Richard Buck, Katherine Gettens, and George Leslie Stout. Chase and Stoner were curious about their subjects’ experiences as conservators during a time of immense change and asked them to discuss their mentors, first jobs, technical approaches to caring for material culture, and thoughts on the future. This roundtable discussion grew into the Foundation for Advancement in Conservation (FAIC) Oral History Project.

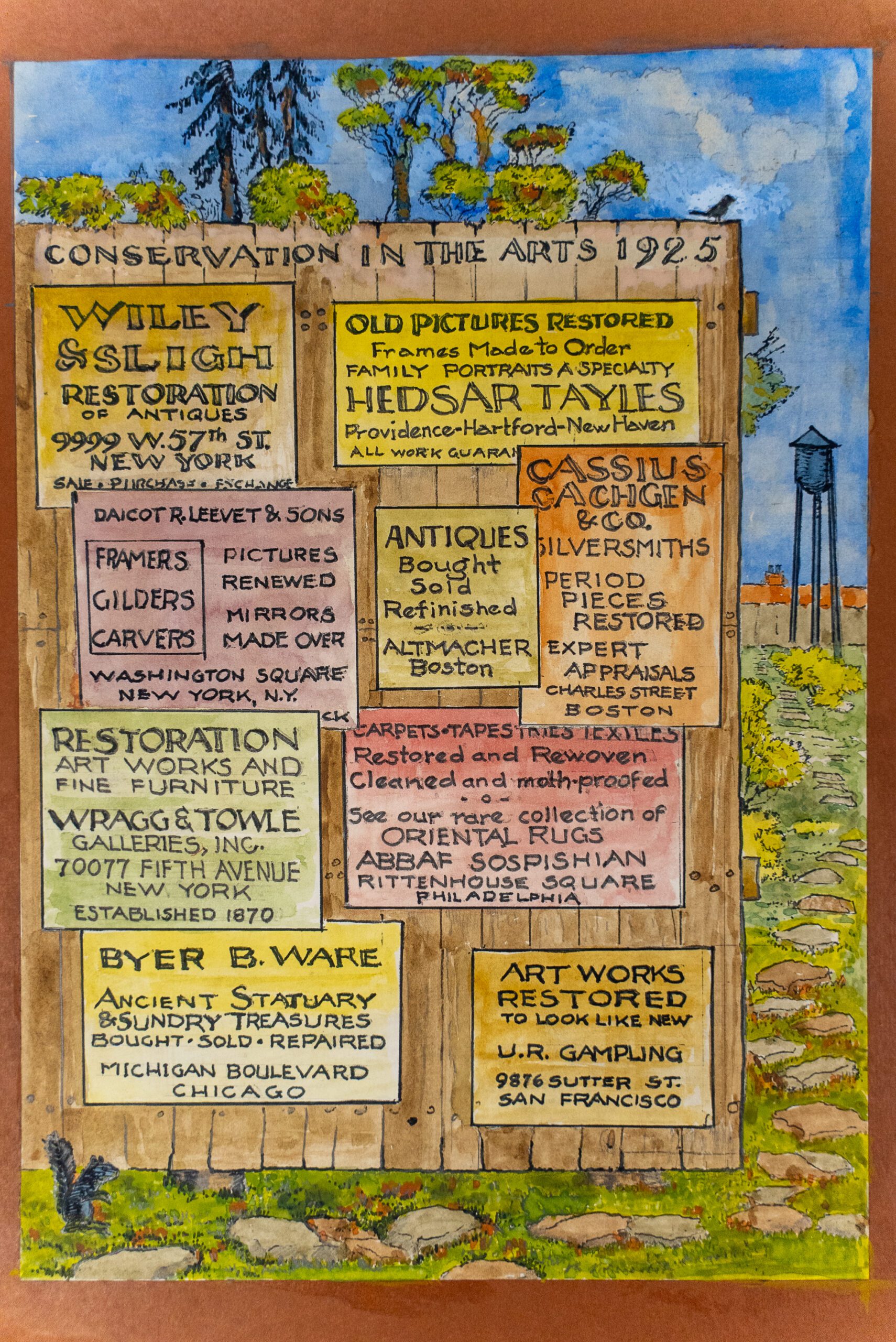

The FAIC Oral History Project documents developments in the field of conservation through firsthand accounts. When the project officially began in 1975, conservation was a relatively recent development in cultural heritage work. Prior to the mid-20th century, historically significant objects that needed treatment in America were typically worked on by restorers who wanted to preserve and restore them to their original state.

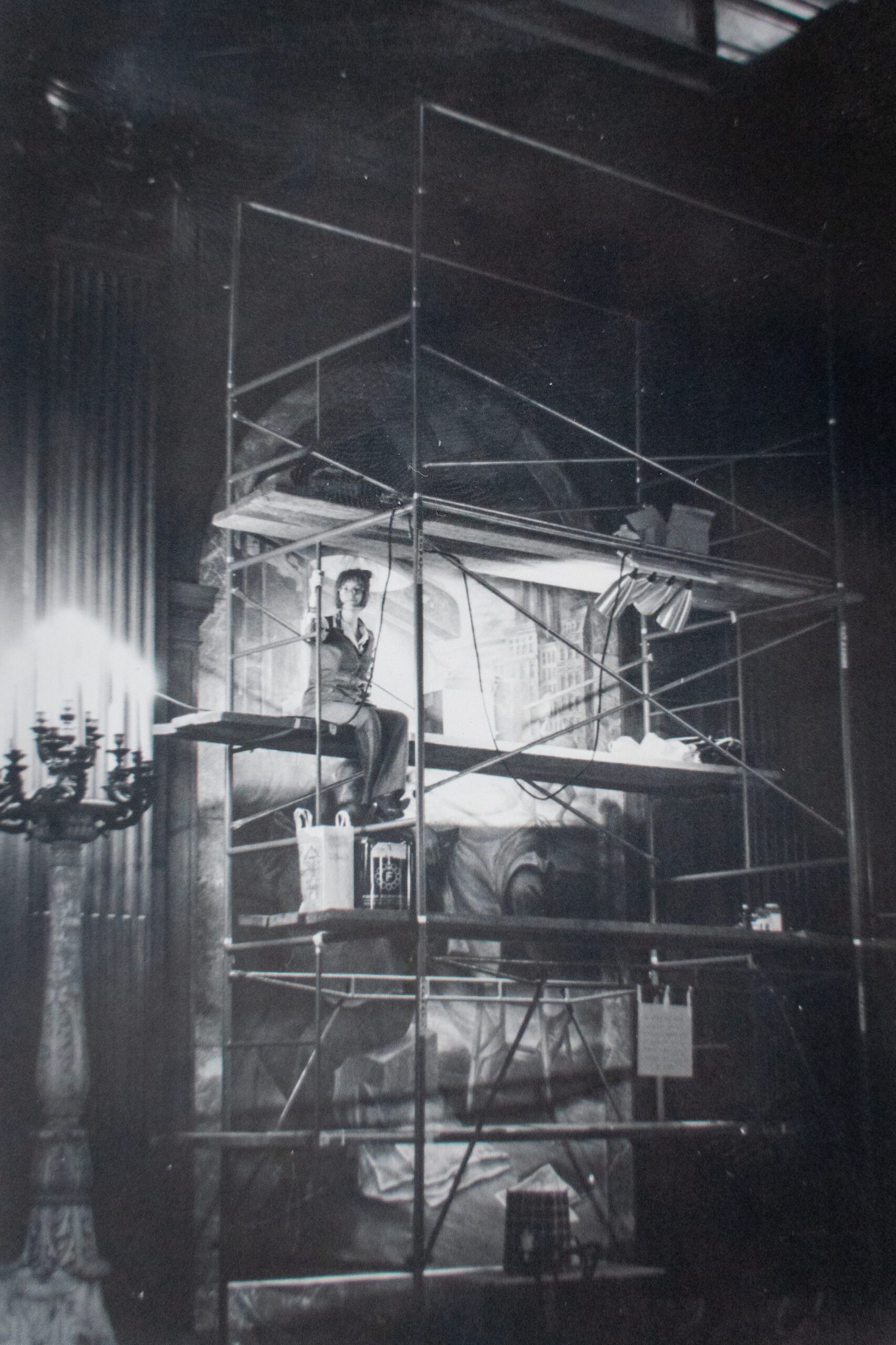

Two events in American history accelerated the transition from restoration to conservation—World War II and Italy’s 1966 Florence Flood. During both events, Americans traveled abroad and joined international experts to recover, repatriate, and provide appropriate treatments on objects of cultural significance. Roundtable interviewee George Leslie Stout served in the “Monuments Men” division of the Civil Affairs and Military Government Sections of the Allied armies during World War II. One of the first Monuments Men to land in Normandy after D-Day, Stout helped conserve thousands of works of art stolen and hidden by the Nazis across Europe.

By the late 20th century, museums, libraries and other cultural institutions hired conservators to work on their collections and ensure the long-term preservation of the objects that connect us to our shared past. Conservators today focus on using reversible treatments and preventing future damage to objects.

Since 1975, hundreds of interviews have been held with conservators and allied professionals in America and abroad. Rebecca Rushfield, associate director of the project, conducted more than one hundred interviews and continues this work today. These interviews provide insights into the history of object treatments, issues in the field, and eyewitness accounts of numerous historical events. Now housed in the Winterthur Library, the FAIC Oral History Collection archive can be accessed online through the Winterthur Library Digital Collection or on-site at the Winterthur Library by appointment.

Explore the digital collection.

Explore the finding aid for the complete collection.

Winterthur thanks the Berger Foundation for supporting work to make this collection accessible to a broad public.