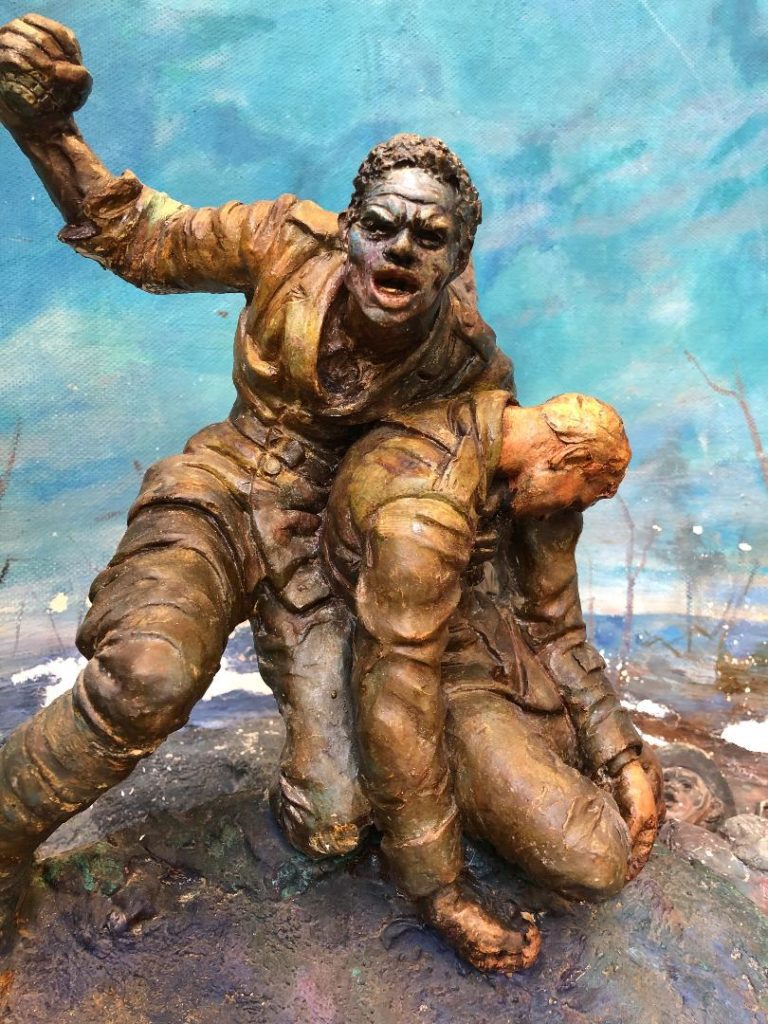

Resting atop a worktable in the Winterthur painting conservation lab is a 4-by-5-foot diorama that depicts three doughboys in the heat of battle during World War I. Two of the figures are Black. One throws a grenade as the other drags an injured white soldier out of harm’s way. The structure beautifully captures a powerful moment of heroism and the character of its subjects.

The 80-year-old diorama, World War I, is the last of 33 created for and displayed at the American Negro Exposition, a World’s Fair-style event, held in Chicago in 1940. The event was organized to celebrate 75 years of emancipation while promoting racial understanding, and was considered to be the first opportunity Black Americans had to tell their story to the world in their own way. The dioramas, displayed in the center of the Chicago Coliseum, depicted the contributions Africans and other peoples of African descent made to world events and culture since black slaves built the Great Sphinx of Giza 4,500 years ago.

World War I may be the last in the series of dioramas, but it is certainly not the end of the story. The 20 surviving dioramas, now in the collection of the Legacy Museum at Tuskegee University, represent almost all that remains to explain an important but almost forgotten event while introducing students of color to the profession of art conservation. Correspondent Rita Braver is scheduled to tell the story during the August 30 episode of “CBS Sunday Morning.”

Supervised by African American artist Charles C. Dawson, the dioramas were created by more than 120 African American artisans in Chicago in just three months of 1940. Beyond the dioramas, the only material records of the American Negro Exposition known to exist are some posters, guidebooks, and catalogues for Exhibition of the Art of the American Negro (1851-1940). About 250,000 people paid 25 cents each to visit during the 60-day run, but due to financial troubles and attendance numbers far short of the 2 million visitors the organizers hoped for, the exposition was considered a failure. But the dioramas still have much to teach.

World War I depicts the bravery of the U.S. Army’s 369th regiment at Meuse-Argonne. Known as the Harlem Hellfighters, the soldiers were especially feared by their German foes. The two standing figures are Needham Roberts and Henry Johnson, who were awarded the first two prix de guerre from the French for their bravery in charging the German lines to rescue their comrades.

The original subtitle to the diorama reads: “Over 380,000 Negro enlisted men and more than 1,500 Negro commissioned officers, with the rank from 2nd Lieutenants to Colonels, participated in this War. They were engaged in all offensives as combat troops and in other capacities. The highlight was the organization and participation as a unit of the first Negro combat division in American history, the 92nd or Buffalo Division. The first Americans to be honored in this war were two Negro Sergeants: Needham Roberts and Henry Johnson of the 369th Infantry Regiment. The most honored of all American regiments was the 369th Regiment of Infantry of New York.”

The diorama, like most of the 19 others delivered to the George Washington Carver Museum (now the Legacy Museum of Tuskegee University) soon after the exposition closed, was damaged in transport. Some were damaged by a fire a few years later, and all suffered from years of neglect in storage. They now offer learning opportunities for young conservators.

There is a critical need for conservators and curators of color. According to the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, African Americans represent about only 1.5 percent of cultural-heritage professionals while Caucasians account for 85 percent. Barriers to entering the field of conservation are significant: There are only a few graduate programs in art conservation in the United States, and to be considered for admission, candidates need to have backgrounds in chemistry, art history, and studio art and ideally 400 hours in a conservation studio showing their patience, dexterity, and problem-solving abilities.

They can gain that experience through the Tuskegee Diorama project/HBCU Alliance of Museums and Galleries internship program. The initiative is headed by Dr. Jontyle Robinson, curator of the Legacy Museum at Tuskegee University who will be featured on the CBS segment, and Dr. Caryl McFarlane, executive consultant of the HBCU Alliance of Museums and Galleries. The pair formed the HBCU Alliance of Museums and Art Galleries in 2017 to promote diversity in the field of cultural heritage. They have been working since 2016 with Debbie Hess Norris, director of the Winterthur/University of Delaware (UD) Program in Art Conservation, and Dr. Joyce Hill Stoner, director of the UD Preservation Studies Doctoral Program and Winterthur’s adjunct paintings conservator. The Kress Foundation has supported the last three years of the diorama initiative.

The effort puts the future of Black history directly in the hands of African American students. As part of the program, Winterthur, the University of Delaware, and several other institutions, such as Yale University, have welcomed a small group of students each June since 2017 for an introduction to practical conservation (the program was delivered online during the Covid 19 pandemic this summer). The students learn by helping to remove grime, consolidate flaking plaster, and in-paint with reversible conservation retouching paints. They also research related topics and listen to presentations by Winterthur conservators in objects, textiles, books, photographs, furniture, works on paper, and preventive conservation.

When World War I arrived at Winterthur, a thick layer of dust and grime disguised its bright blue and red overall color scheme and the plaster ground was flaking. Johnson’s grenade arm had broken off; it arrived separately in a small box. Since January, other conservation interns have continued to consolidate the flaking paint and plaster, painstakingly removing decades of dust and dirt with small cosmetic sponges, correcting a repair made in 1945, and re-attaching Johnson’s arm. When finished in early 2021, the diorama will be returned to the Legacy Museum for display in the ongoing exhibition 20 Dioramas: Brightly-Lit Windows, Magically Different.

The first three dioramas that were treated at Winterthur depict the arrival of the first African slaves in Virginia in 1619, the shooting of Crispus Attucks in the Boston Massacre (the first death of the American Revolution) in 1770, and discovery of the North Pole in 1909 by explorer Matthew Henson accompanying Admiral Robert Peary. Scheduled to arrive next year is a diorama that depicts the towing of the Sphinx, which allows Winterthur and the University of Delaware the privilege of preserving the beginning and the end of the diorama stories as these objects move into their new future.

Look for more on CBS Sunday Morning on August 30.

Winterthur is further helping to train young conservators of color through the HBCU Library Alliance Preservation Internship Program, an eight-week, paid internship for seven students at seven different, nationally recognized library conservation labs. Each site contributes 50 percent of the cost for each intern, including travel, a stipend for living, and other support. Other participants in the program include Yale, Harvard, Duke, and the Library of Congress. That is tremendous support for young people from some of the most esteemed institutions in the country. It is coordinated by Winterthur library and archives conservator Melissa Tedone.