By Allie Alvis, Curator of Special Collections

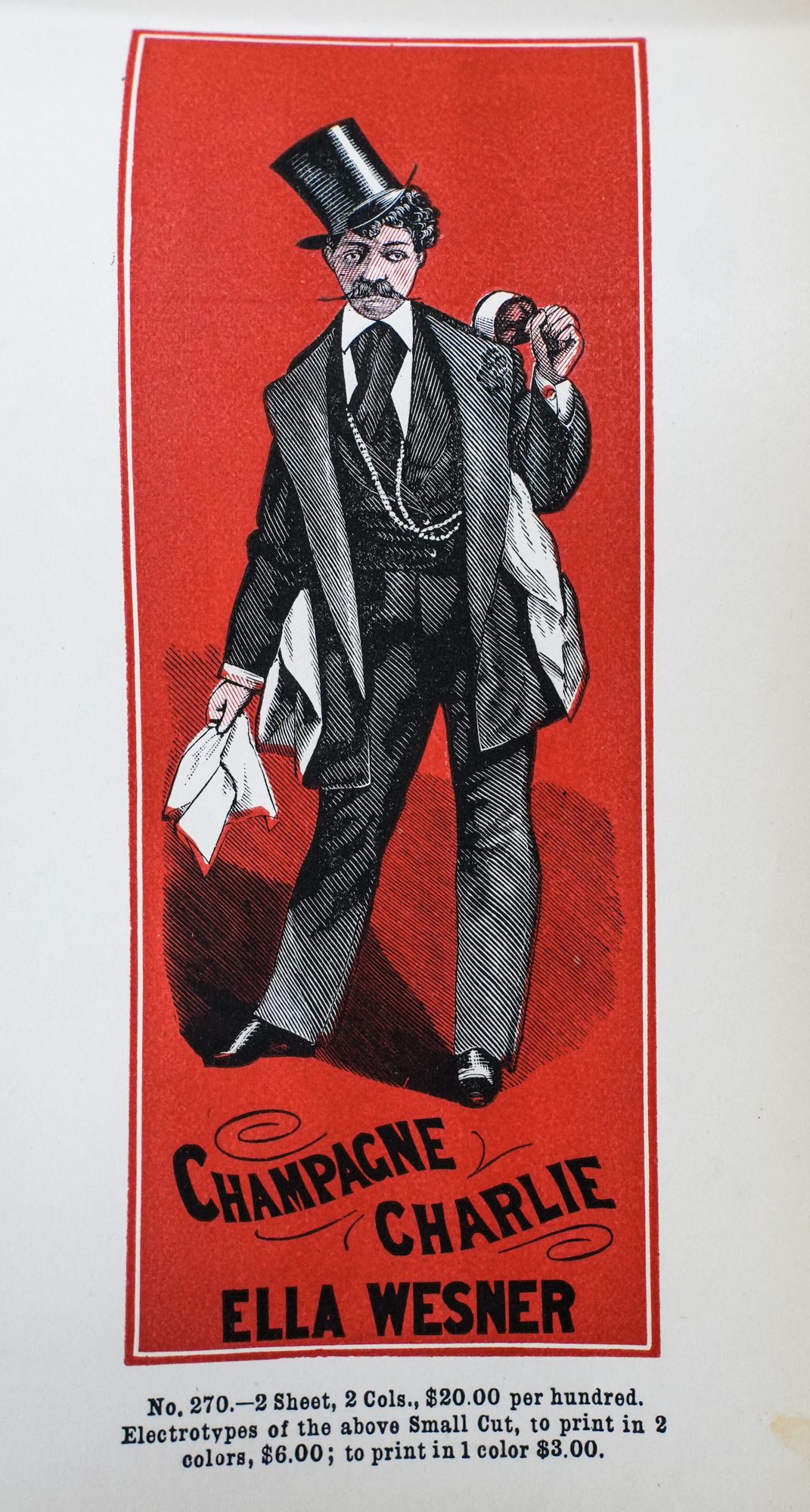

Imagine that you, a young Victorian lady, are spending a night out with friends at the theater. As the playhouse dims, a spotlight illuminates the figure of Champagne Charlie, the picture of swaggering, stylish masculinity. Charlie captivates the audience with amusing tales of chivalry and his ability to please women, accompanied by a parade of chorus girls in “bright but somewhat abbreviated habiliments.”1 You swoon; if only you could find a man like that! But that would be difficult—for, you see, Champagne Charlie is a woman by the name of Ella Wesner.

The drag show is not a modern phenomenon. In fact, the term “drag” likely dates to the stages of Elizabethan England, referring to male actors playing women’s roles in plays including those of Shakespeare.2 And almost as soon as women were legally allowed to be professional actors on the English stage in the mid-17th century, there emerged the “breeches role”—a male part written for or cast as a woman, who would don a masculine costume.

At various points, laws and edicts banned the practice of performing roles outside one’s gender, but the intrepid players persisted, and some even used this restriction as a marketing tool. The roving variety entertainers of the 19th century refined their response into the male impersonator act.

Ella Wesner (she/her) was one such performer at the peak of her fame in the 1870s and ‘80s. Born in Philadelphia in 1841 to a family of actors and dancers, Wesner began her career in ballet and performed “Bel Demonio” in 1864 alongside Felicita Vestvali, who acted in a breeches role in the show.3 Wesner watched Vestvali and learned and later earned a place as a dresser for Annie Hindle, the first male impersonator to make it big in America.

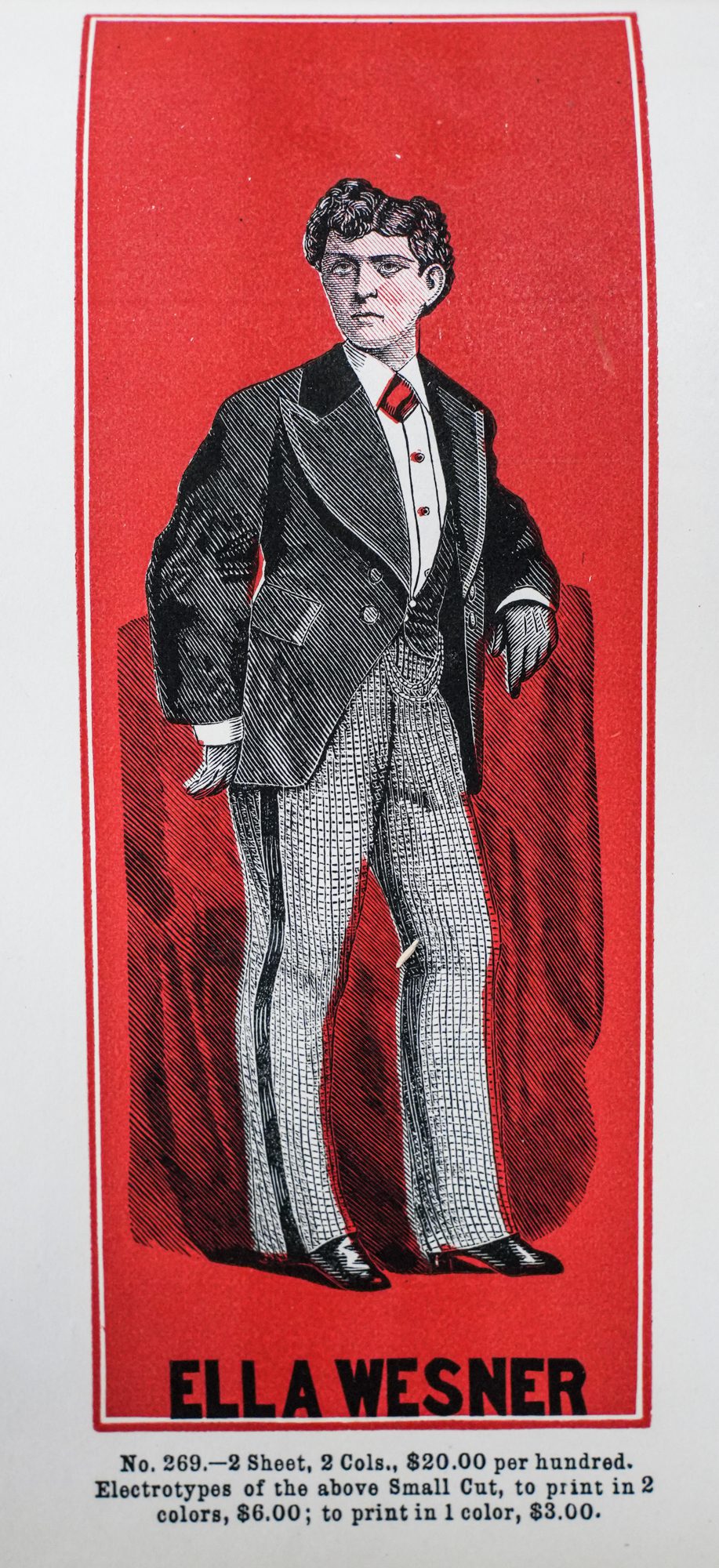

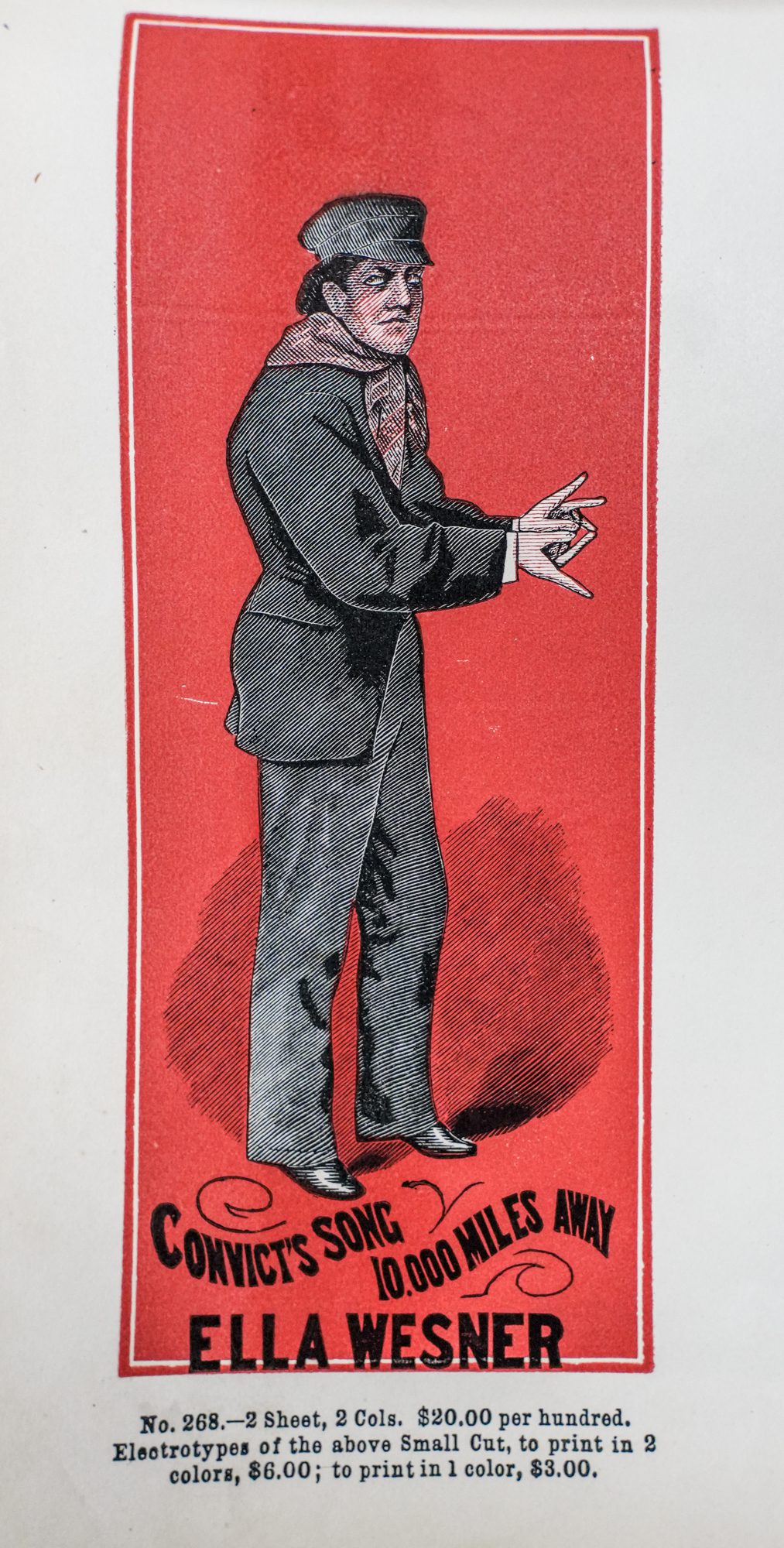

Wesner made it big herself in 1870, sauntering across stages as male characters, including the debonaire Champagne Charlie, the cigarette-smoking Sweet Caporal, Jinks the Jovial Showman, and the amusingly drunk Teetotal. Reviews proclaimed her “a Beau Brummell par excellence” 4 and “an excellent man upon the stage,”5 and she became one of the highest-paid variety performers of the period.6 An 1870 review of her act celebrated her “almost faultless form, a face quite masculine and jet black curling hair, which she wears cut short.”7 Her success was the result of not just hard work, but of advertising. This is where the Winterthur Library comes in.

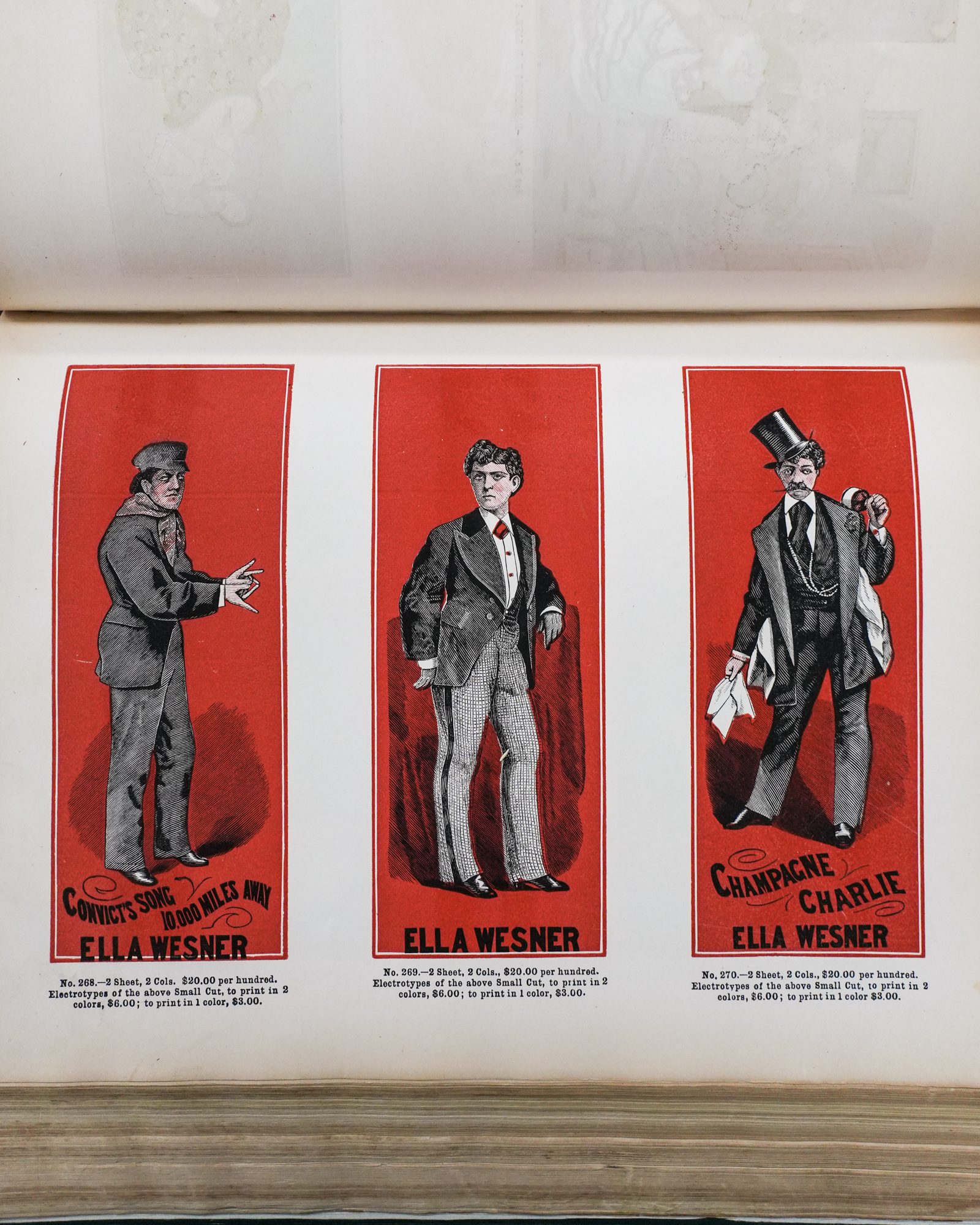

The library special collections holds a copy of an 1872 trade catalog titled Specimens of Theatrical Cuts, which is a compendium of thousands of illustrations produced by the Philadelphia-based Ledger Job Printing Office. These illustrations were created to be used by newspapers, theaters, and various other agents to advertise the acts and shows coming through town. Many were quite formulaic and could be used for any play or performance that even vaguely touched upon the dramatic or comedic scenes depicted. Among these stock images are illustrations of particularly well-known performers of the day, including four different depictions of Ella Wesner.

Her inclusion in this volume speaks not just to how prolific Wesner was as a performer, but to her dominance of the genre in the 1870s. Her illustrations are all captioned with her name, making it impossible to reuse them to advertise other male impersonators. Although her career had several ups and downs—at one point, she ran off to Paris with the mistress of a robber baron—her act was deeply influential for later generations of male impersonators, including Vesta Tilley and Ella Shields.

Wesner didn’t just dress as a man onstage; she “preferred men’s apparel” throughout her life and was buried in a suit per her request.8 This physical evidence of Wesner’s fame is one of many LGBTQIA+ stories found in the library collections.

Sources:

1. “Yesterday’s Concerts.” Clipping. 1885. Digital Transgender Archive, https://www.digitaltransgenderarchive.net/files/6q182k40p

2. David A Gerstner. Routledge International Encyclopedia of Queer Culture. London: Routledge, 2006, page 191.

3. Gillian M. Rodger. Just One of the Boys: Female-to-Male Cross-Dressing on the American Variety Stage. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2018, pages 35–36.

4. Tom Gillen. “DO YOU REMEMBER?” Clipping. 1926. Digital Transgender Archive, https://www.digitaltransgenderarchive.net/files/wp988k17c

5. “MISS ELLA WESNER, The Acknowledged Beau-ideal of Society Entertainment, Surnamed ‘THE CAPTAIN.’.” Clipping. 1910. Digital Transgender Archive, https://www.digitaltransgenderarchive.net/files/bg257f356

6. “OUR VARIETY ARTISTS.” Clipping. 1881. Digital Transgender Archive, https://www.digitaltransgenderarchive.net/files/gt54kn32b

7. Catherine Smith and Cynthia Greig. Women in Pants: Manly Maidens, Cowgirls, and Other Renegades. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2003, page 90.

8. “Ella Wesner Lies in Man’s Garb.” Clipping. 1917. Digital Transgender Archive, https://www.digitaltransgenderarchive.net/files/xg94hp908