By Matthew Monk, Linda Eaton Associate Curator of Textiles at Winterthur

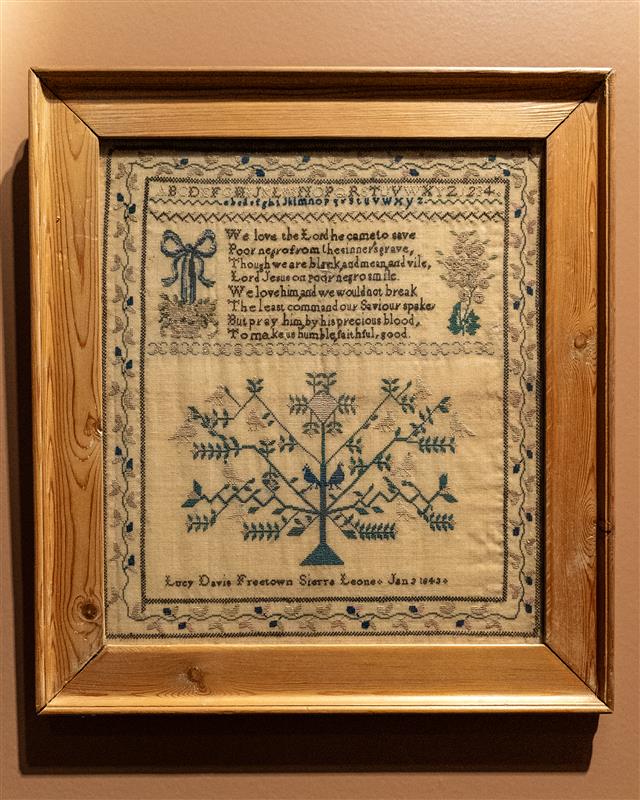

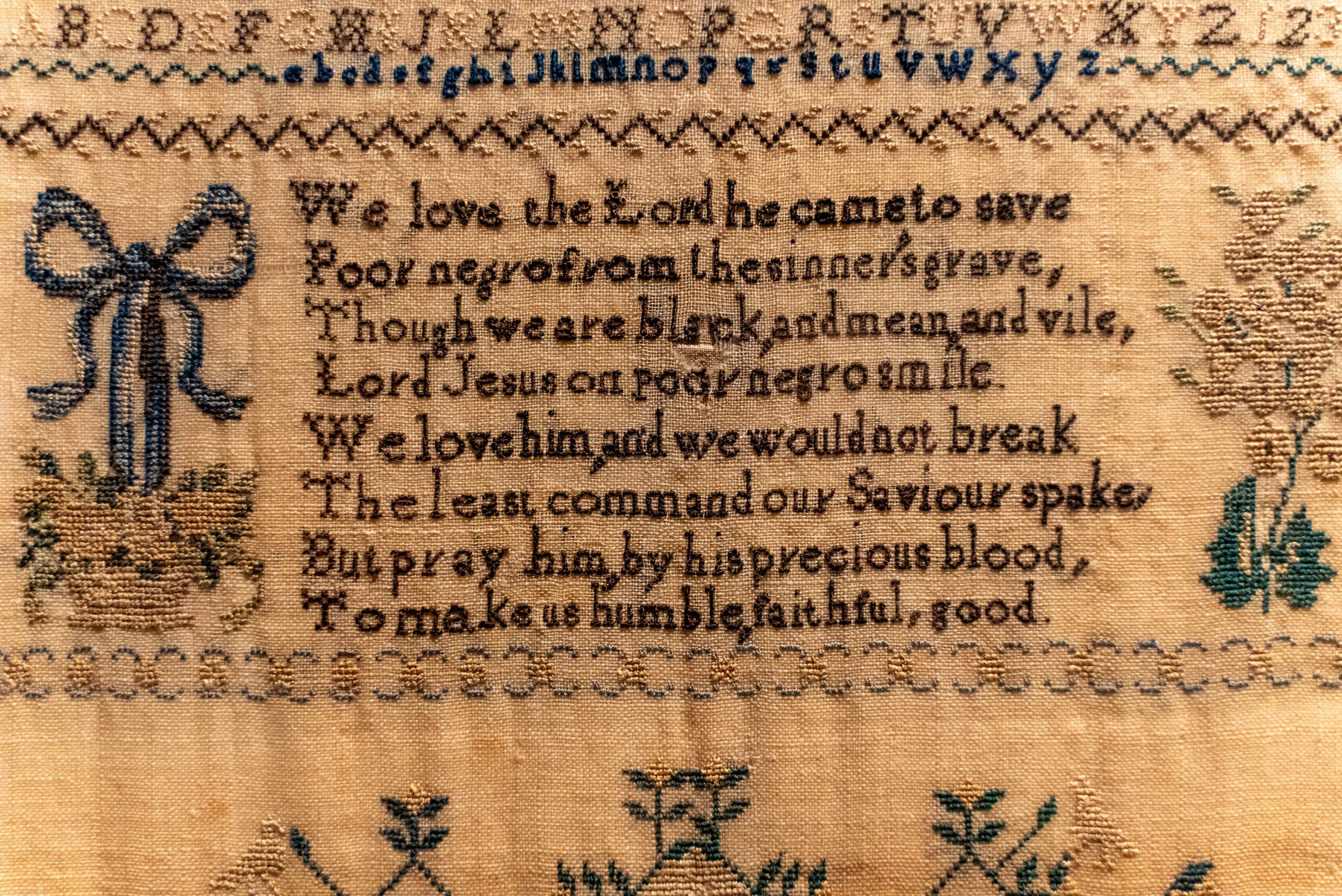

On January 3, 1843, Lucy Davis, a Black African girl, completed this sampler at a Church Missionary Society (CMS) school in Freetown, Sierra Leone. Her needlework features a central field divided by a cross-stitched border of repeating X motifs. The upper half contains a verse from Hymn for a Poor Negro, a poem printed in The Missionary Repository for Youth, and Sunday School Missionary Magazine.1 Missionaries across the expanding British Empire used literature like this to Christianize and anglicize African youth and reinforce British colonial hierarchies of race and class:

“We love the Lord he came to save

Poor negro from the sinner’s grave,

Though we are black, and mean, and vile,

Lord Jesus on poor negro smile.

We love him, and we would not break

The least command our Saviour spake,

But pray him, by his precious blood,

To make us humble, faithful, good.”

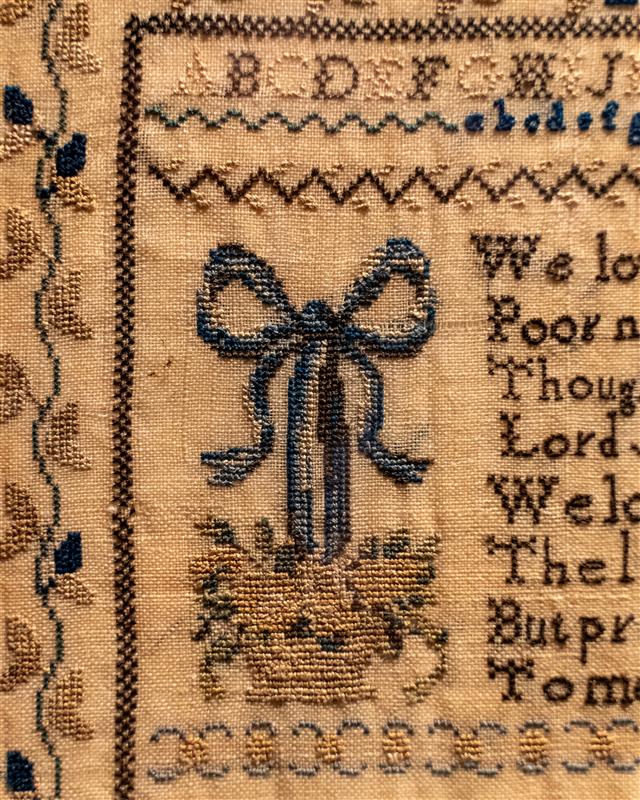

Flanking the verse are a basket of flowers tied with a bow on the right and a spray of blooms on the left. The lower half of the linen ground features a stylized tree filled with birds with Davis’s name, location, and the date stitched below. A leafy vine border, framed by long-arm cross stitches, surrounds the entire composition.

Only twenty-six samplers from CMS schools are known to survive, and few student records exist beyond the needlework itself. However, one teacher’s name is known: Jane Hickson Boston Young (1810–1841), a Eurafrican woman educated at a CMS school in the Rio Pongo region (now the Republic of Guinea). Jane learned needlework from an African American colonist—referred to only as “Nova Scotian”—who had remained loyal to Britain during the American Revolution and later immigrated to British-controlled Africa from Nova Scotia.2

Jane Young went on to teach at CMS schools in Kissy, Gloucester, Bathurst, and eventually Freetown and Waterloo, where she and her second husband founded a school in 1836. Though she died in 1841, just two years before Davis stitched her sampler, it’s likely that Davis was taught by a liberated African woman who had been trained by Young—continuing a lineage of needlework instruction that began with a formerly enslaved African American woman.3

CMS schools were established to educate native-born Africans and “recaptives” or “liberated Africans”—those freed by the British Navy after the Empire banned the transatlantic slave trade in 1806. These children were relocated to Sierra Leone and educated in CMS schools, often sponsored by British abolitionists. By the 1830s, the schools primarily served native-born Sierra Leoneans, and after Jane Young’s death, the needlework teacher in Freetown and Waterloo was likely one of these liberated African women whose name has been lost to history.4

Lucy Davis’s sampler reflects both the constraints and the aspirations of colonial education. While the verse and format were shaped by British missionary ideals, Davis’s work also represents the emergence of an educated Sierra Leonese elite—young Black Africans who were being trained for roles within the colonial administrative structure. Her sampler embodies the paradox of colonial education: devotional verse stitched in thread, at once reinforcing racial hierarchies and preserving the presence of Black girls in the historical record and is featured in our exhibition Almost Unknown, The Afric-American Picture Gallery.

Sources:

- Periodical Publications. 1839. “The Missionary Repository for Youth, and Sunday Scholar’s Book of Missions.” In Nineteenth-Century Short Title Catalogue.

- Silke Strickrodt, PhD, “Mission Samplers from Sierra Leone: Traces of a Black Woman’s Career in the Church Missionary Society, c. 1811 to 1841,” Spotlight: In-Depth Dive into Noteworthy Needlework. Samplings.com (Philadelphia: M. Finkel & Daughter, 2025); Silke Strickrodt, “African Girls’ Samplers from Mission Schools in Sierra Leone (1820s to 1840s),” History in Africa. 2010;37:189-245.

- Strickrodt, “Mission Samplers from Sierra Leone.”

- Ibid.