By Dr. Jonathan Michael Square

Faustin Soulouque plays a central role in my exhibition at Winterthur—Almost Unknown, The Afric-American Picture Gallery. While Toussaint Louverture is the more familiar figure featured in “Afric-American Picture Gallery,” the 1859 essay by William J. Wilson that serves as the foundation of Almost Unknown, Soulouque was the reigning monarch of Haiti when the essay was published. His reign, which began in 1847 and culminated in his self-coronation as Emperor Faustin I in 1849, marked a period of intense visual and political spectacle. While some saw him as a symbol of Black empowerment and resistance to neocolonial influence, others—both in Haiti and abroad—viewed his rule as a caricature of monarchy and a descent into despotism.

Known for his affinity for ritual, ceremonial dress, and imperial pageantry, Soulouque cultivated a public image that exuded opulence and authority. This is vividly captured in a posthumous portrait of him featured in what I call the “Haiti section” of the exhibition. The painting is one of fifteen oil portraits of Haitian heads of state completed by artist Louis Rigaud between 1877 and 1881. The portraits were exhibited at the World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition in New Orleans and were acquired by the Smithsonian in 1885. However, the portraits were determined to be of questionable value because they were assessed through a Western art-historical framework that privileged originality, formal innovation, and linear notions of artistic development. The Smithsonian transferred them to the Yale Peabody Museum in 1963, where they remain in the museum’s collection as an important visual archive of Haitian political history.

Wilson describes Soulouque as “a superior looking man,” which speaks to his physical appearance and the aura of regality that he projected. In Rigaud’s painting, Soulouque is depicted in full regalia, wearing a vivid red military coat adorned with medals and gold epaulettes, as well as a blue sash. Like his public persona, his garments were strategic visual assertions of Black sovereignty in the post-emancipation Atlantic world, designed to reframe the terms of power, liberation, and legitimacy on Haiti’s own terms.

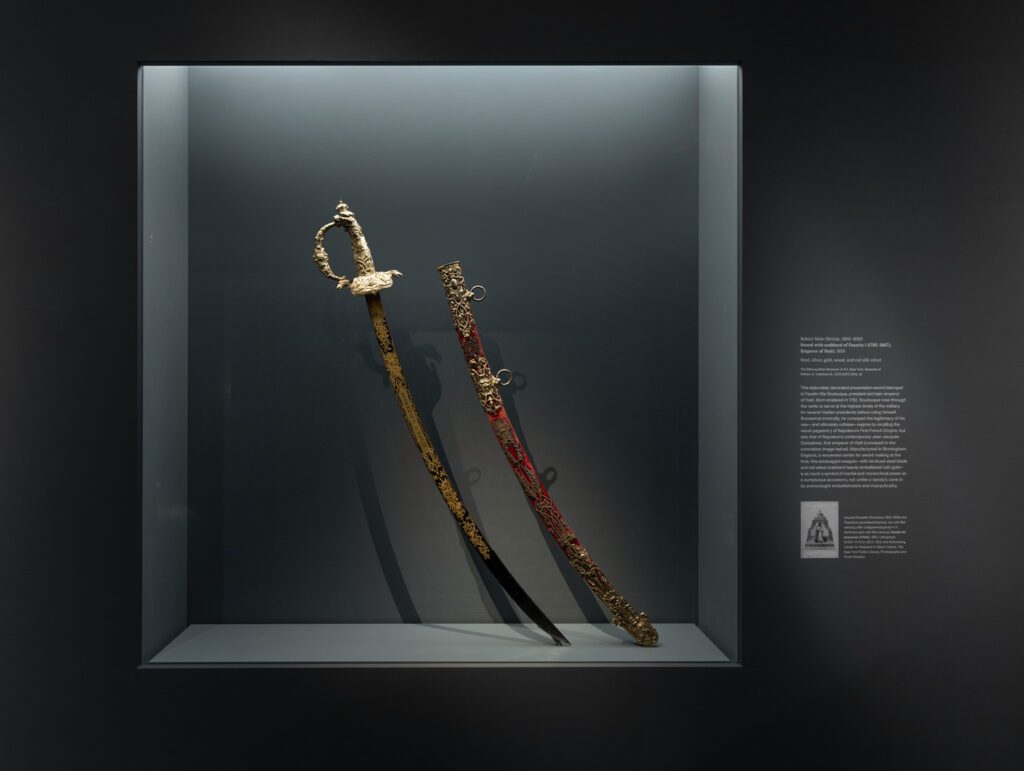

One of the most striking artifacts that further illuminates Soulouque’s political performance through dress is a ceremonial sword presented to him by the Grand Masonic Lodge of Haiti in 1850. Later gifted to US Consul Henry Delafield, this opulent weapon functioned as a diplomatic gesture and an emblem of imperial authority. It is currently on display in my exhibition Superfine: Tailoring Black Style, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where it helps frame a conversation about the global entanglements of Black fashion, political aesthetics, and statecraft.

Faustin Soulouque’s legacy, both in terms of his image and material culture, offers a powerful counternarrative to the dominant Western histories of sovereignty. His visual performance of power is essential to understanding the intersection of fashion, freedom, and Black political imagination.

Experience Almost Unknown, The Afric-American Picture Gallery on view in the Winterthur Galleries through January 4, 2026.