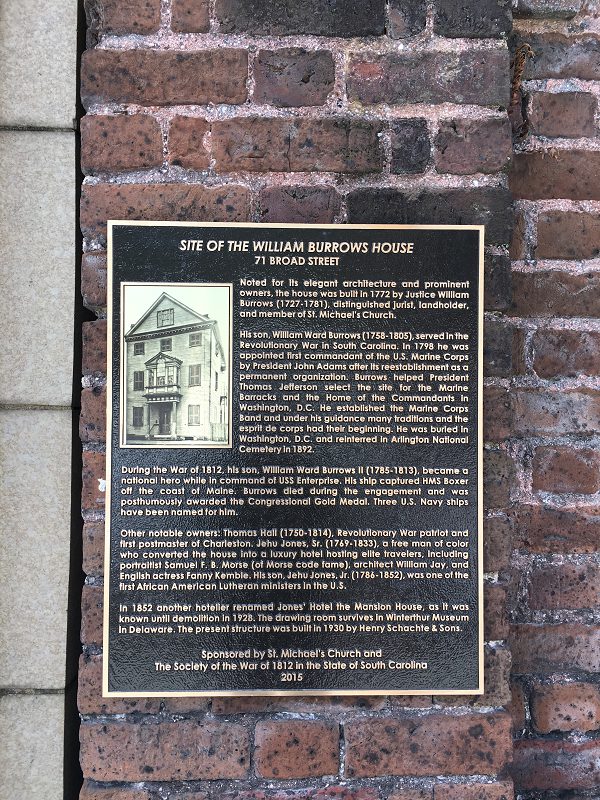

Although not currently on a tour, the Charleston Dining Room on Winterthur’s third floor contains woodwork and windows from what was once a fashionable gathering place in antebellum South Carolina. The 18th-century paneling, cornices, fireplace and mantel, and windows are from a hotel that stood in Charleston near the intersection of Broad and Meeting Streets. During its heyday in the 1820s and 1830s, the hotel hosted visitors from across America and Europe.

“Every Englishman who visits Charleston,” wrote one foreign guest in 1833, “will, if he be wise, direct his baggage to be conveyed to Jones’s hotel.” The Old World elegance of its dinners included iced claret that “might have converted even Diogenes into a gourmet.”(1) Another guest was Samuel F. B. Morse, who was then known as a painter rather than as an inventor. Around 1821, Morse came to Charleston and rented rooms behind the Jones Hotel to serve as a portrait studio.

Both guests would have spent time in the Charleston Dining Room. Located on the second floor of the hotel’s main building, it probably functioned not as a dining room but as a drawing room, where guests might gather after meals. The bay window projected over the main entrance on Broad Street, giving guests a clear view of city hall.

The Jones Hotel was also just a few hundred feet from the headquarters of Charleston’s city guard. After nine o’clock at night, the guard would arrest black residents, whether enslaved or free, who ventured out of doors. A German duke staying at the hotel around 1825 recounted hearing a warning call from inside his room, noting that he was “startled to hear the retreat and reveillé beat there.”(2) The Joneses, for all their importance to the social life of the elites—and although they were slaveholders themselves—were among the people being targeted.

What is now the Charleston Dining Room may be the only identifiable surviving part of the main hotel. The building fell into disrepair in the late 19th century and around 1928, it was dismantled and placed in storage. Some pieces, including the paneling in this room, were eventually acquired by the Yale University Art Gallery, where Henry Francis du Pont discovered them in the 1950s. The sections that made up the room were shipped from New Haven and installed at Winterthur, originally serving as a lunch spot for visitors taking all-day tours.

The warm sandy color of the walls is based on the earliest original layer of paint, applied around 1774 when the hotel was constructed as a private home. The white tiles lining the fireplace suggest the patterned Delft tiles popular in Charleston at the time. What comes from the building itself is the carved wood—including the windows, the elaborate decorations above the fireplace, and the two closet doors. The entrance, however, was moved from its original location opposite the bay window in order to fit the current space.

Post by Jonathan W. Wilson, a historian and adjunct faculty member at the University of Scranton and Marywood University.

NOTES

(1) Thomas Hamilton, Men and Manners in America, vol. 2 (Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood and T. Cadell, 1833), 278.

(2) Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar Eisenach, Travels through North America, during the Years 1825 and 1826, vol. 2 (Philadelphia: Carey, Lea & Carey, 1928), 7.

SELECTED REFERENCES

Amrita Chakrabarti Myers, Forging Freedom: Black Women and the Pursuit of Liberty in Antebellum Charleston (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011), 99–100.

Albert Simons, “Report of Matters Pertaining to the Removal of the Mansion House, Charleston, South Carolina,” n.d., Winterthur Archives.

Harriet P. Simons and Albert Simons, “The William Burrows House of Charleston,” Winterthur Portfolio 3 (1967): 172-203.

“Jehu Jones: Free Black Entrepreneur,” 1989, Public Programs Packet no. 1, South Carolina Department of Archives and History.

John A. H. Sweeney, The Treasury House of Early American Rooms (New York: W. W. Norton, 1963), 12, 76–77.

Marina Wikramanayake, A World in Shadow: The Free Black in Antebellum South Carolina (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1973), 79, 103–111.