What started as simple research into a silhouette in the Winterthur collection progressed to a three-month trek through directories, census records, newspaper advertisements, maps, artist encyclopedias, archives, and auction catalogs. The silhouette in question, a group portrait against an interior in watercolor, has proved to be fascinating, and research has discounted previous scholarship as a new story emerges.

Silhouettes were popular and cheap forms of portraiture throughout the 18th century and into the 19th century. During the period, they were referred to as “shades” or “profile miniatures,” though by the early 19th century they are just described as “profiles.” (1) There are various ways to produce these profiles, though the most talented artists could cut freehand, such as the most prolific 19th-century silhouettist Auguste Édouart.(2) Originally from France, Édouart traveled extensively through Great Britain and America creating some 100,000 silhouettes, keeping a copy or record of each one he produced. Winterthur has some examples of Édouart’s work.

Other silhouettists could sketch from life or use a mechanical device like a physiognotrace to capture the profile.

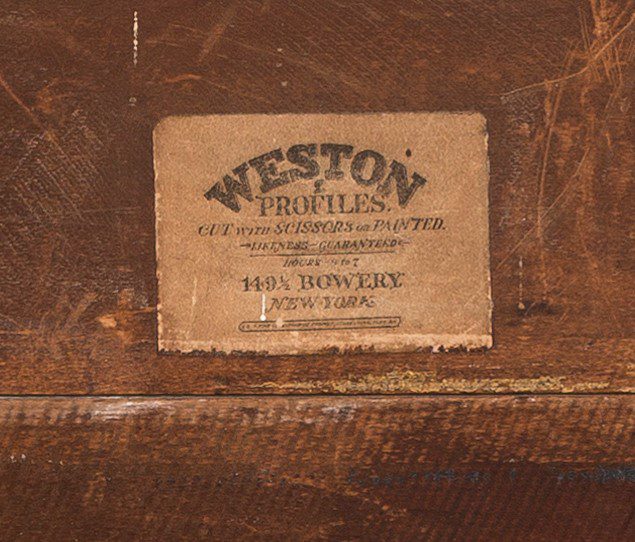

While many silhouettes feature one figure, this piece contains seven cut silhouettes painted black with white and tinted highlights to delineate details on the clothing and accessories. Underneath these figures the viewer can read the names of the Dennison and Barcley family and a “Miss Lucy Dale.” In the bottom right corner, the silhouette is signed “Weston pinxt./ 149 ½ Bowery.” On the reverse of the frame, an affixed label also gives the address 149 ½ Bowery. Winterthur’s records cited Mary Bartlett Pillsbury Weston as the artist, though a letter in the records from 1957 indicated that no Weston had been found in the New York City Directory at the Bowery location in the 1840s. From here, the questions grew.

Conducting genealogical research on Mary Pillsbury Weston, I discovered a captivating tale of a woman determined to be an artist. Born in Hebron, New Hampshire, in 1817, she was the daughter of Baptist minister Stephen Pillsbury and Lavinia Hobart. Texts from the 19th century recount Mary Weston’s romantic tale: a deep yearning as a child to paint and how she ran away two times in an attempt to become an artist, finally moving to Willington, Connecticut, in 1837, painting portraits of local families. While in Connecticut, she met New Yorker Valentine Weston, brother to Willington citizen Jonathan Weston. Valentine invited Mary to come to New York, where he would employ artists to continue to instruct her and help her become an artist. After three months of living in New York, Mary married Valentine in 1840.(3) Mary Weston lived in New York until after her husband’s death in 1863.

Regardless of any tentative ties to Édouart, texts from the 19th century only claim that Mary was a portrait and landscape artist. There is no evidence that she ever made silhouettes and that is supported by archival research. The Kenneth Spencer Research Library at the University of Kansas holds the Pillsbury Family Papers, which contain Mary Weston’s outgoing letters from 1840 to 1867. While Mary wrote about painting and selling her work, she never mentions a silhouette business.

For most researchers, labels on objects are considered a gift. Other times, they only make the piece more confusing, as in the case of the Weston profile. Valentine Weston, 32 years Mary’s senior, appears in the New York City Directory as a blind maker, frame maker, and looking glass maker as early as 1822 and into the 1840s. His son from a previous marriage, John L. Weston, also owned a frame-making business in that same period continuing into the 1850s. Frame makers frequently sold prints and drawing in their store, thus it would not have been a leap to assume that Mary had a deal with her husband and son-in-law to create framed silhouettes for clients. However, at no point are these two men ever listed at 149 ½ Bowery, and their businesses stayed within the lower west side.

At this point, it seems unlikely that Mary Bartlett Pillsbury Weston ever made and sold silhouettes. Who was the Weston who created this silhouette? Who are the sitters? How do we know that this is even from the 1840s? These questions will continue to be pursued in part two, which will be posted on next week!

You can see this silhouette and others from the Winterthur Library and museum collection in the special loan exhibition In Fine Form: The Striking Silhouette at the Delaware Antiques Show, November 9–11, 2018.

Post by Amanda Hinckle, Robert and Elizabeth Owens Curatorial Fellow, Museum Collections Department, Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library

Winterthur is very grateful for funding from the National Endowment for the Arts, which has given us the ability to photograph and digitize works on paper in the collection, including these silhouettes.

(1) Emma Rutherford, Silhouette: The Art of the Shadow (New York: Rizzoli, 2009), 21.

(2) Rutherford, Silhouette, 29.

(3) E.F. Ellet, Women Artists in All Ages and Countries (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1859); H. W. French, Art and Artists in Connecticut (Boston: Lee and Shepard, Publishers; New York: Charles T. Dillingham, 1879); and Augusta Harvey Worthen, The History of Sutton, New Hampshire: Consisting of the Historical Collections of Erastus Wadleigh, Esq., and A. H. Worthen (Concord, NH: The Republican Press Association, 1890).