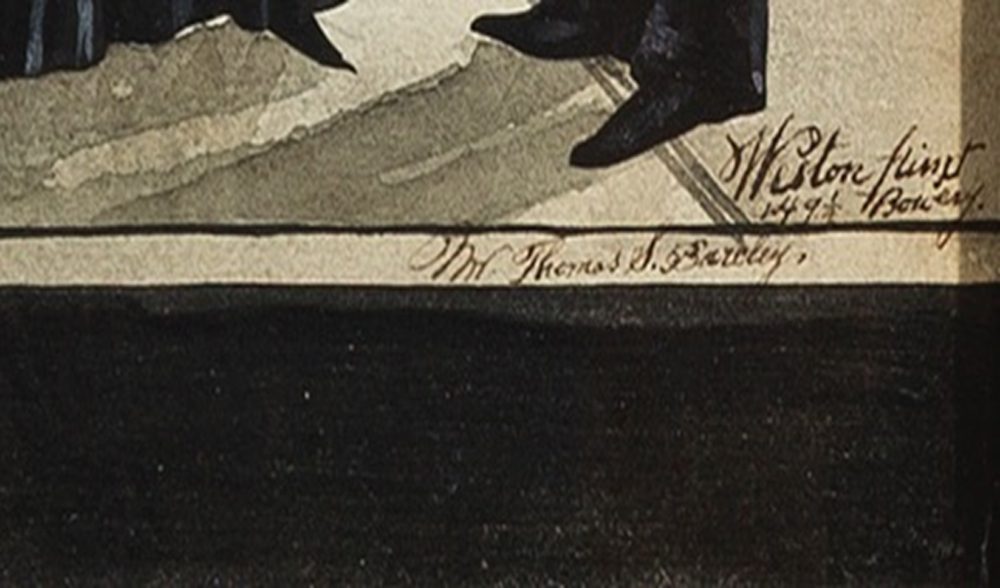

In the first Silhouette Sleuthing blog post, I detailed how I discovered that one of the silhouettes in the Winterthur collection had been misattributed to artist Mary Pillsbury Weston, who was most famous for her Spirit of Kansas painting exhibited at the Columbian Exhibition. There is no evidence to suggest that she ever produced and sold silhouettes. If the Weston profiles were not created by Mary, then who created them? I started to look through auction catalogs for other Weston silhouettes, hoping to understand the artist’s style. I found other pieces attributed to Weston, many of which are signed and contain the “Weston Profiles” label on the rear of the frame. Two types of signatures appear. The first, similar to the silhouette in the Winterthur collection, is a handwritten, cursive script with “Weston pinxt./149 ½ Bowery.” It can be found on a full-length silhouette of a woman, which was sold at auction by Northeast Auctions in 2015. (1) Other examples have a block-lettered serif signature “Weston of NY,” sometimes including the date. The two signatures could indicate that different individuals created these silhouettes under the name “Weston Profiles.”

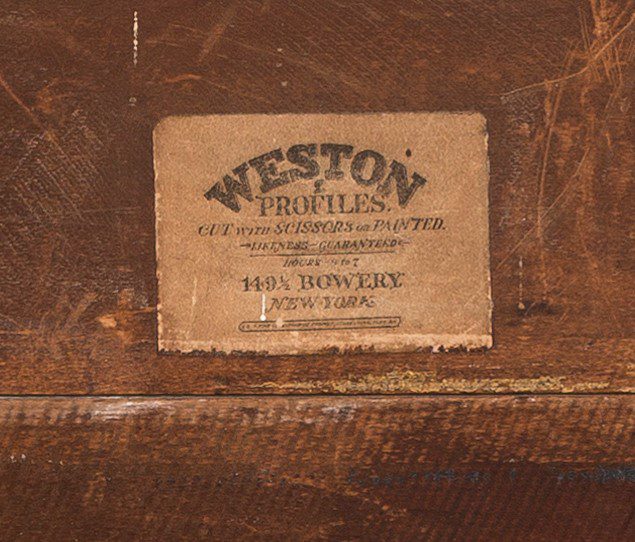

Since most of the silhouettes have a “Weston Profiles/149 ½ Bowery” label attached to the back of the frame, it indicates that they have a common source. However, this does not solve the mystery of the address, since no Westons have been found at 149 ½ Bowery, as discussed in the previous blog post. Could these silhouettes be fake? Winterthur Paper Conservator Joan Irving examined the Weston profile in the frame, and there were no red flags to suggest it was not produced in the 19th century. However, she did note that the label appeared to have been cut down at some point. This does not mean that the silhouette is fake, it is possible the piece was reframed at some point and the label reaffixed to the new frame.

If we accept the material evidence that these silhouettes were made in the 1840s, and there are no known Westons living on Bowery at this time, who or what was at 149 ½ Bowery? The only reference to a 149 ½ Bowery found in primary sources is J. Wilson Fancy Goods Store listed in the New York Mercantile Union Business Directory in 1850. This reference seemed promising since a silhouettist could have operated out of a fancy goods store. J. Wilson, however, could not be traced to that location prior to 1850 in Trow’s New York City Directory. Looking at what businesses worked out of 149 Bowery during the 1840s, I found a distillery, leather working, and saddlery at this location. The leather business is possibly the closest connection, since cases for miniatures, silhouettes, and daguerreotypes typically utilized leather, and I found a group of Westons who operated a daguerreotype business in the city. This group of Westons can be found in the New York City directories during the period of production, and they include a John P. Weston, a Robert Weston, and another Mary A. Weston—all of whom were daguerreotypists. This was a promising avenue because the career jump from silhouettist to daguerreotypist would not have been surprising in the period. Silhouettes were a cheap, quick, and easy way to produce form of portraiture, some even employing the physiognotrace or pantograph machines, which are considered forerunners to photography. (2) Boundaries between what we understand as “fine artist” and “daguerreotypist” were fluid with some artists producing both artwork and daguerreotypes at the same time, and others using the technology to help with their artwork. Photography eclipsed silhouettes in the mid-19th century as a more accurate and equally easy method to produce mode of portraiture. According to the directories, James P. Weston operated in New York City as a daguerreotypist from 1842 to 1857. In 1842, James partnered with artist William Hendrik Franquinet to create a series of daguerreotype views of the city of New York and continued to work as a daguerreotypist throughout the 1840s and into the 50s. (3) Unfortunately, James P. Weston disappears from the records after 1857. The husband and wife pair, Robert and Mary A. Weston, were also in the daguerreotype business. The 1850 Federal census lists English-born Robert Weston as an artist, while the 1855 New York Census reports that he worked with daguerreotypes. (4) Mary’s profession is never listed in either census. Possibly blood relatives, Robert Weston and James P. Weston were listed together at 132 Chatham and 192 Broadway as daguerreians through the 1840s and 1850s. Mary Ann Weston was the daughter of British immigrant Thomas Kearsing (1774–1856), a pianoforte maker of the well-known Kearsing piano makers from the 1830s. She was born around 1812 in New York City, and she married Robert in 1839. She only appears in the directories between 1858 and 1861, where the couple were listed separately at 142 ½ Bowery. After Robert’s death in 1863, Mary continued to operate as a photographer at 392 Bowery until 1866, as seen in the U.S. IRS Tax Lists. (5) By 1866, Mary looked to move to California, posting in the New York Daily Herald: A PHOTOGRAPH GALLERY, ESTABLISHED IN THIS city in 1839, and in a flourishing state of business, to be sold as the owner must leave for California to settle some family affairs. Apply at WESTON’S Photograph Gallery, 392 Bowery, near Cooper Institute.[v] She eventually moved to California in 1874 to be with her siblings, where she died three years later. The Westons operated close to the 149 ½ address. Their closest relation to this address lies with a leather factory. In 1845, James P. Weston used the address 43 Eldridge for his daguerreotype submission to the American Institute and the Mechanics’ Institute Art Fair, an address he shared with Walter S. Abbott of Abbott & Smith Saddlery. Between 1842 and 1843, Abbott & Smith Saddlery is located at 149 Bowery. Did the two men know each other? Could Weston have operated a studio out of Abbott’s shop? Did Abbott make cases for Weston? These three Westons are the likely makers of the silhouette in the Winterthur collection. James and Robert exhibited works in the American Institute annual fairs. Robert submitted a “pen & ink drawing” at the 1846 show, (6) showing that he had the ability to produce at least the silhouette’s background. If Robert, his wife, and James were in business together, that could account for the different styles in signature and silhouettes that are found on Weston Profiles, i.e. block serif script versus cursive script. None of the silhouettes have a first name included in the signature but that is similar to the daguerreotypes produced by the Westons, which can be found in the New-York Historical Society, the J. Paul Getty Museum, and in auction houses. These pieces usually include the name “Weston” and the studio address across the bottom of the frame.

While research concluded that Mary Pillsbury Weston was not the creator of the Weston Profiles, another Mary Weston was most probably involved. The Westons produced silhouettes in the 1840s, and as the daguerreotype became more popular and more accessible to a larger market, they diversified by opening a daguerreotype studio. By the end of the decade and into the 1860s, they started to create photographs and carte-de-visites, continuing to stay abreast of consumer demands. They did not garner the notoriety like famous daguerreotypists Matthew Brady or Jeremiah Gurney, nor did they operate on their scale. In fact, New York City was filled with studios like the Westons’. In 1853, it was estimated that there were 86 portrait galleries in the city. (7) More research needs to be conducted on these smaller enterprises to get a better sense of the operations of a portrait-making and -selling business like the Westons’, and its relationship to a larger network of material production in mid-19th-century New York. You can see this silhouette and others from the Winterthur Library and museum collection in the special loan exhibition In Fine Form: The Striking Silhouette at the Delaware Antiques Show, November 9–11, 2018. Post by Amanda Hinckle, 2017-2018 Robert and Elizabeth Owens Curatorial Fellow, Museum Collections Department, Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library Winterthur is very grateful for funding from the National Endowment for the Arts, which has given us the ability to photograph and digitize works on paper in the collection, including these silhouettes. (1) Northeast Auctions. Fall Weekend Auction, October 31-November 1, 2015.Portsmouth, NH: 2015. Auction Catalog. https://northeastauctions.com/product/mary-pillsbury-weston-american-1817-1894-full-length-silhouette-of-a-woman-circa-1840/ (2) Emma Rutherford, Silhouette: The Art of the Shadow (New York: Rizzoli, 2009). (3) J Winchester, “Daguerreotype Portraits,” The New World: A Weekly Journal 5 (November 26, 1842): 351. (4) Although not in the New York City directories until 1848, the arrival of a Robert Weston is reported in the New-York Spectator in 1837, which is backed by immigration records. “Passengers,” New-York Spectator, March 28, 1837. (5) Craig’s Daguerreian Registry, last modified 1998, http://craigcamera.com/dag/. (6) New York Daily Herald, March 17, 1866, 7. (7) Ethan Robey’s dissertation titled “The Utility of Art: Mechanics’ Institute Fairs in New York City, 1828-1876,” includes an appendix listing artists who displayed their work. Ethan Robey, “The Utility of Art: Mechanics’ Institute Fairs in New York City, 1828-1876” PhD diss., Columbia University, New York, 2000. (8) Beaumont Newhall, The Daguerreotype in America, 3rd ed. (New York: Dover, 1976), 55.