“Ann Lowe was an exemplary creator in American fashion who happened to be Black. While this was, no doubt, an important part of her identity, it was only one part. Lowe was a spectacular and multidimensional American fashion designer, and I wanted the exhibition music to reflect other amazing Black artists like her who excelled in their genre. Her work was classical and generally structured, while also embracing organic elements, especially flowers. She was highly technical but prioritized beauty and elegance. I wanted the music to convey these elements of her work.” -Elizabeth Way, guest curator of Ann Lowe: American Couturier

Inspired by Ann Lowe: American Couturier, this playlist celebrates Black creative excellence in fields that are traditionally homogenous with barriers to people of color.

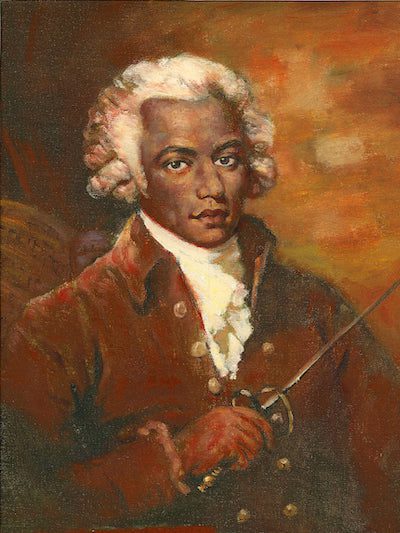

We begin the playlist with Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges, a Black Creole man who is considered the first classical composer of African descent to receive critical acclaim. Born in 1745 in the Caribbean French colony Guadeloupe, Saint-Georges’s father was a wealthy, white landowner and his mother was an enslaved Black woman on the estate. In 1769, he joined the French orchestra of the Concert des Amateurs as a violinist and became the orchestra’s concertmaster and conductor in 1773. Saint-Georges was a popular choice to take over the Paris Opéra, but several singers sent a letter of protest to Queen Marie Antoinette over his election to the position because they did not want to receive orders from a Black man. While Saint-Georges did not become the leader of the Paris Opéra, he was invited to be one of the private musicians of Queen Marie Antoinette. From 1771 to 1779, Saint-Georges composed and published numerous operas, string quartets, concertos, and symphonies, performing all his violin concertos as the soloist with Le Concert Olympique, an orchestra he also conducted. One of the most well-known creative ventures of Saint-Georges was his commission of Haydn’s Paris Symphonies: Saint-Georges asked Haydn to write six symphonies for his orchestra, which were then premiered and conducted by Saint-Georges.

The next musician on the playlist is Florence Beatrice Price, born Florence Beatrice Smith in Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1887. She is credited as being the first Black woman to be recognized as a symphonic composer with a major composition played by a notable orchestra. In 1930, a significant early success kicked off Price’s musical career as a composer: at the twelfth annual convention of the National Association of Negro Musicians, pianist-composer Margaret Bonds premiered Price’s Fantasie nègre [No.1] (1929). In 1931, Price and her husband divorced, leading her to living with Margaret Bonds. While living with Bonds, Price became friends with Langston Hughes and Marian Anderson, prominent figures in the art world who assisted with Price’s future success as a composer. In 1933, Maude Roberts George, president of the Chicago Music Association, paid for Price’s First Symphony to be included in “The Negro in Music” program in the Century of Progress World’s Fair. Price’s First Symphony was performed by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Frederick Stock, making Price the first Black woman to have her work played by a major U.S. orchestra.

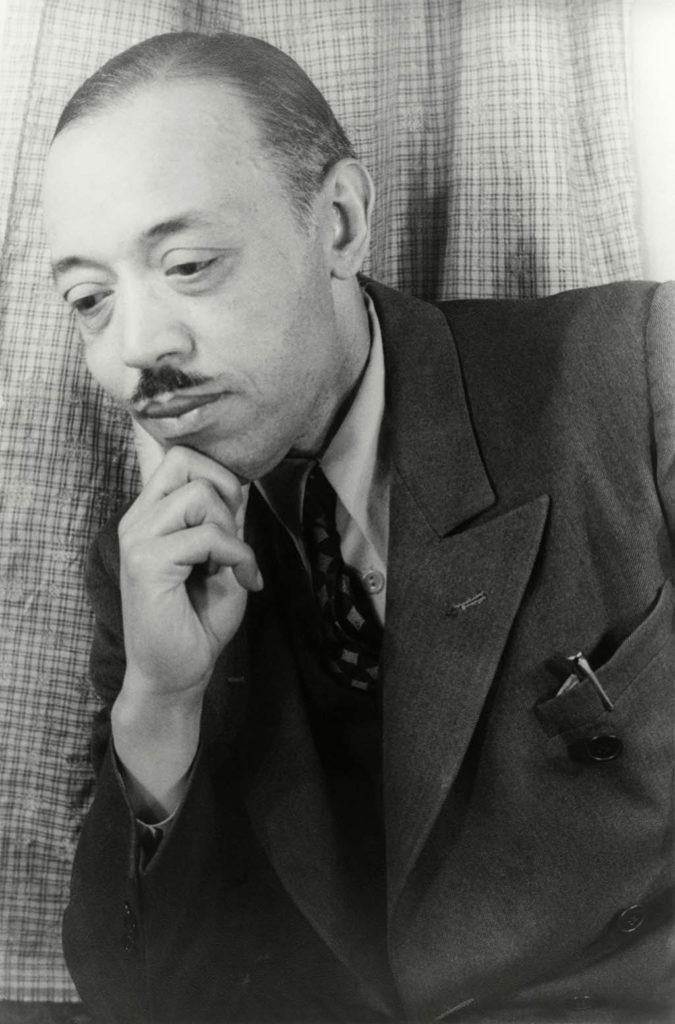

Next up is William Grant Still Jr., a Black composer of nearly 200 works from Little Rock, Arkansas. Known as the “Dean of Afro-American Composers,” Still was the first American composer to have an opera produced by the New York City Opera. His most well-known work is his first symphony, Afro-American Symphony (1930), which was the most widely performed symphony composed by an American until 1950. By the end of World War II, this work had been performed in orchestras located in New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, Berlin, Paris, and London. In 1936, Still conducted the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra at the Hollywood Bowl, making him the first Black composer to conduct a major American orchestra in a performance of his own works.

One of Florence Beatrice Price’s peers is next on the playlist: Margaret Bonds, who is most well known for her arrangements of African American spirituals and her frequent collaborations with Langston Hughes. Born in 1913 in Chicago, Bonds’s parents were involved in the civil rights movement and the National Association of Negro Musicians. During high school, Bonds studied piano and composition with Florence Beatrice Price. Bonds attended Northwestern University, where she earned her Bachelor of Music and Master of Music in piano and composition. While attending Northwestern, the environment was incredibly hostile and racist, with Bonds being one of the few Black students. During her studies, Bonds found solace in the poem, The Negro Speaks of Rivers by Langston Hughes. Bonds met Hughes in 1936 and during her career, she set much of his work to music.

Next on the playlist is James Hubert “Eubie” Blake. Born in 1887 in Baltimore to formerly enslaved individuals, Blake is known as a pianist and composer of ragtime, jazz, and pop music. His musical training began when he was four or five years old, when he wandered into a music store and began “fooling around” on an organ. When his mother found him, the music store manager said that Blake was a musical genius and that it would be criminal to deprive him of an outlet. Blake’s first major break in the music industry came in 1907 when world champion boxer, Joe Gans, hired him to play the piano at Gans’ Goldfield Hotel in Baltimore. Shortly after World War I, Blake formed a vaudeville musical act with performer Noble Sissle. The two began working on a musical revue called Shuffle Along, which incorporated their songs and had a book written by F. E. Miller and Aubrey Lyles. Shuffle Along premiered on Broadway in 1921 and became the first hit musical on Broadway written by and about Black individuals.

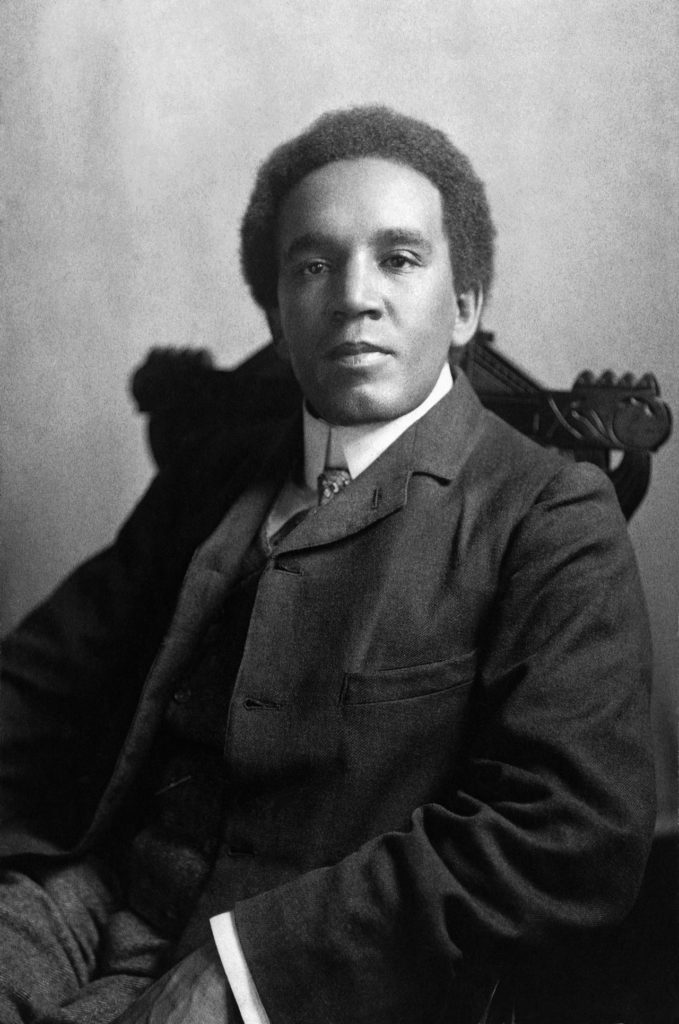

Following Eubie Blake on the playlist is Samuel Coleridge-Taylor. Coleridge-Taylor was a Black British composer and conductor born in 1875, often referred to as the “African Mahler” by white New York musicians. By 1896, Coleridge-Taylor was beginning to earn a reputation as a composer. In 1898, Coleridge-Taylor completed his most well-known work: three cantatas based on the poem The Song of Hiawatha by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. After the popularity of his work on The Song of Hiawatha, Coleridge-Taylor made three tours of the United States, where he became interested in his paternal racial heritage. He was the youngest delegate at the 1900 First Pan-African Conference in London, where he met many prominent Black Americans, like Paul Laurence Dunbar and W. E. B. Du Bois. During his first tour of the United States in 1904, Coleridge-Taylor was received by President Theodore Roosevelt, a very rare event for a Black man. Coleridge-Taylor was well-known for his endeavor to integrate traditional African music into the classical style of music.

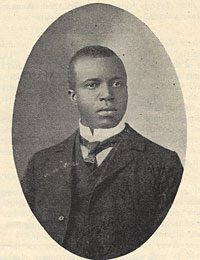

Closing out the playlist is Scott Joplin, the “King of Ragtime.” Born in 1868 in Texas, Joplin was a composer and pianist, most well-known for his “Maple Leaf Rag,” which is credited as being the first and most influential ragtime hit. Joplin considered ragtime to be a form of classical music, inventing the genre as a blend of classical music, the musical atmosphere in which he grew up—work songs, gospel hymns, spirituals, and dance music—and his own natural ability. Like many of the artists on this playlist, Joplin combined traditional Black musical styles with European forms and melodies. Joplin put his unique blend of Black folk music’s syncopation and 19th-century European romanticism on the map at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair.

All these artists, like Ann Lowe, excelled in their fields, creating works that were groundbreaking and genre-bending and still resonate with listeners centuries later. Their identities as Black individuals shaped their experience as artists, often creating larger hurdles for them to overcome, but regardless of this fact, they all changed the course of music history in their own ways.